THE 1992 Booker Prize-winning novel ‘The English Patient’ by Michael Ondaatje features a character named Kip, an Indian Sikh sapper tasked with clearing explosive mines and bombs in the Second World War. Apart from being subsequently made into a blockbusting movie, Ondaatje’s novel brought light to the vast number of British colonial subjects who participated in the conflict in European battlefields, a fact rarely central to the vast number of books and movies that same war inspired, nor one much highlighted in history books.

David Diop’s novel covers not entirely dissimilar terrain, focusing on the huge number of West African soldiers (some estimates place the number at more than two million) who fought for France in the First World War, mostly on the front where their dark skin and unexpected appearance were calculated to terrify the German troops.

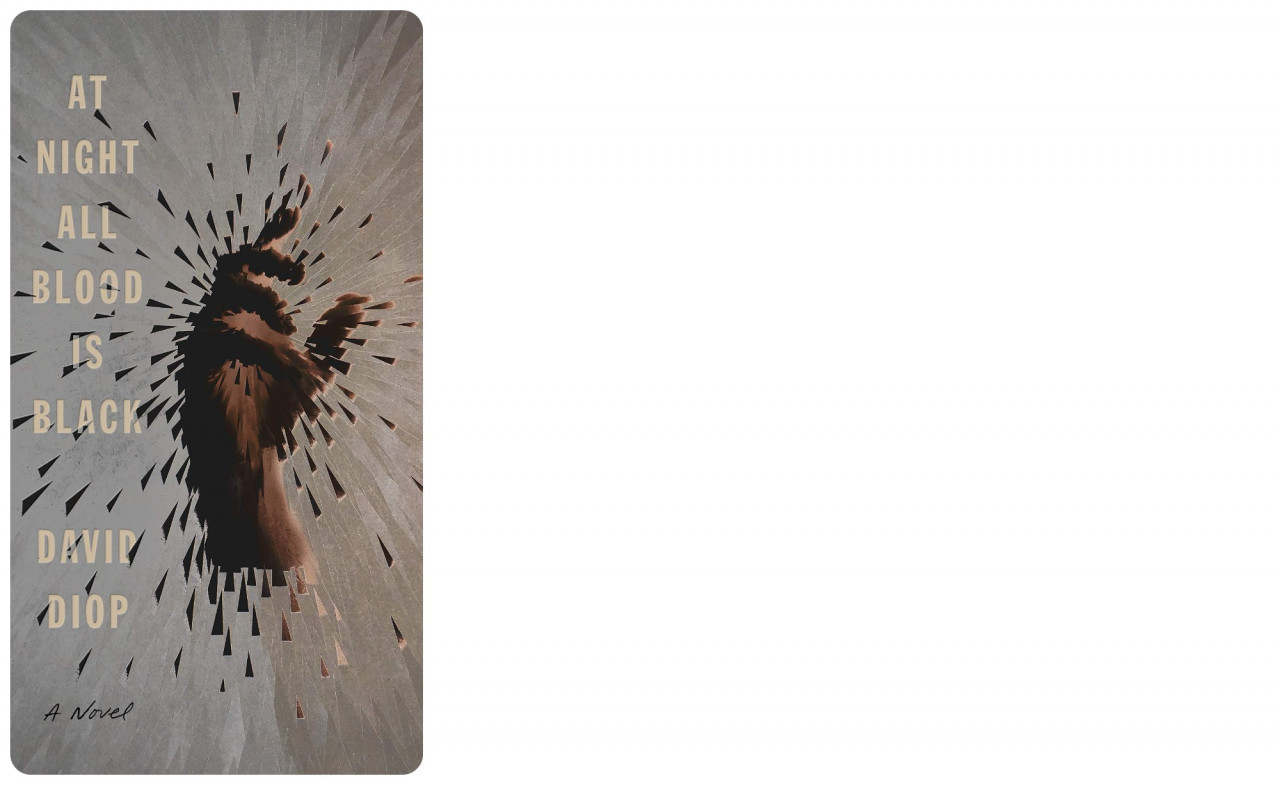

Originally published in French as ‘Frère d'âme’ (literally ‘Soul Brother’) Diop’s novel has won the Prix Goncourt des Lycéens, the Europese Literatuurprijs, and the Premio Strega Europeo.

Translated into English by US translator Anna Moschovakis, who has previously translated George Simeon, Annie Ernaux, Robert Bresson, and Marcel Proust, the novel has a new title, ‘At Night All Blood is Black’ taken from a line in Diop’s book. It is one of the thirteen books longlisted for this year’s International Booker Prize.

More than a century has passed since the end of the First World War, but in the past year we have been persistently reminded that the Spanish Flu killed more people than all its battles, a fact which while shocking, and meant to underline the deadly threat of a pandemic, might be erroneously interpreted as minimising the sheer horror and cost of human life of that war.

Diop’s novel is a timely reminder of just how appalling a war it was, with military tactics from another age that were unequal to the increasing mechanisation of death with its artillery and poisonous gases, men mindlessly sent to be mown down by machine gun fire as they tried to advance across the battlefield.

In many cases there was a stalemate, with enemies on either side sheltering in trenches, with a muddy cratered hellish no-man’s land between, littered with the putrefying bodies of the fallen.

From page one we are immersed into the sheer awfulness of life and death on the front, with the latter often being preferable to the former for many of the wounded who had to endure their injuries being gnawed by rats even if they made it back to the uncertain safety of the trenches where annihilation could come at any moment from mortar and cannon fire.

Diop spares no details. ‘At Night All Blood is Black’ is very far from the tales of heroism that are often a staple of novels glorifying the battlefield. Instead it is relentless, using repetition to hammer home the unbearable reality the characters must endure.

Being told in the first person by narrator Alfa Ndiaye, it very effectively portrays the immediacy of the soldiers’ situation, life lived, or if not lived barely survived, or not, as the case may be, from moment to moment.

Alfa sees his friend and soul brother Mademba Diop dying, having been disembowelled by a German soldier’s bayonet. Mademba begs Alfa to put him out of his misery, but Alfa cannot bring himself to kill his childhood friend. Instead he stays with Mademba until the bitter end, then carries his corpse back to the trenches, rather than leave it to fester where Mademba fell.

For this act of bravery Alfa is awarded a medal and hailed as a hero by his fellow troops, a mix of African and French soldiers who must obey Captain Armand’s whistle or face the consequences.

When some of them mutiny, they learn exactly what those consequences are. Hands tied behind their backs they are forced up the ladders to the battlefield to be picked off by German riflemen. Those who refuse, face execution and the denial of any military pension for their wives or family. One of the mutineers awkwardly scales the ladder announcing that at last he has a reason to face the enemy, that at least his death will serve to support his wife. His head is blown off while calling out her name.

Meanwhile, Alfa has more or less lost his mind. He hatches a plan to avenge his best friend and proceeds to abduct German soldiers, who he then ties up and disembowels in the same way Mademba was made to suffer his final moments. But regretting that he hadn’t heeded Mademba’s pleas to kill him immediately, he gives the German soldiers the quick death their eyes beg for, in a warped way rewriting his friend’s final hours and redeeming himself for having failed to act.

After each foray Alfa returns to the trenches physically unscathed, bearing the twin trophies of a German soldier’s gun and a severed hand.

There are no atheists in foxholes. At first the other African soldiers see Alfa as a totem of good luck, marvelling at his exploits and how he can return with his macabre souvenirs again and again against the odds. But soon that admiration turns to fear and distrust. By the time Alfa has collected eight hands none of his fellow combatants even want to look at him.

Knowing that Alfa’s exploits are affecting troop morale, Captain Armand orders him to withdraw from combat and recuperate for a month. Alfa retreats with his gruesome haul of cured and salted hands.

After this relentless onslaught, for both the narrator and the reader, the novel changes tone and sees Alfa turning his mind to his past in his native Senegal, his first love, and his parents, with an ending that is more satisfying than the reader might expect, given the overall bleakness that precedes it.

‘At Night All Blood is Black’ is a short novel, mercifully so, but one that loudly speaks, not just of the unacceptable violence of war, but the violence inherent in colonialism. – The Vibes, April 17, 2021