IT is difficult to picture what life might be like 4,000 years from now, or even in 40 years. But imagine a scenario where someone living in the year 6021 finds your old school homework and studies it to understand how language was written and used in the early 21st century.

This is essentially what archaeologists and linguists have done in reverse, with the discovery of hardened mud tablets that show the homework of schoolchildren learning to write in the ancient cuneiform script.

Paper is more fragile, though in the right conditions can still endure. But digital school homework is unlikely to last or be subject to future scholarly scrutiny. These relics have been preserved for four millennia due to the nature of the material used. When the ancient Sumerian on those tablets, and countless others, was finally deciphered, it doubled the span of recorded human history, extending our knowledge to times as distant to those described in Latin and Ancient Greek as they are to us now. Nowadays experts can even spot where budding Sumerian scholars made mistakes in their homework.

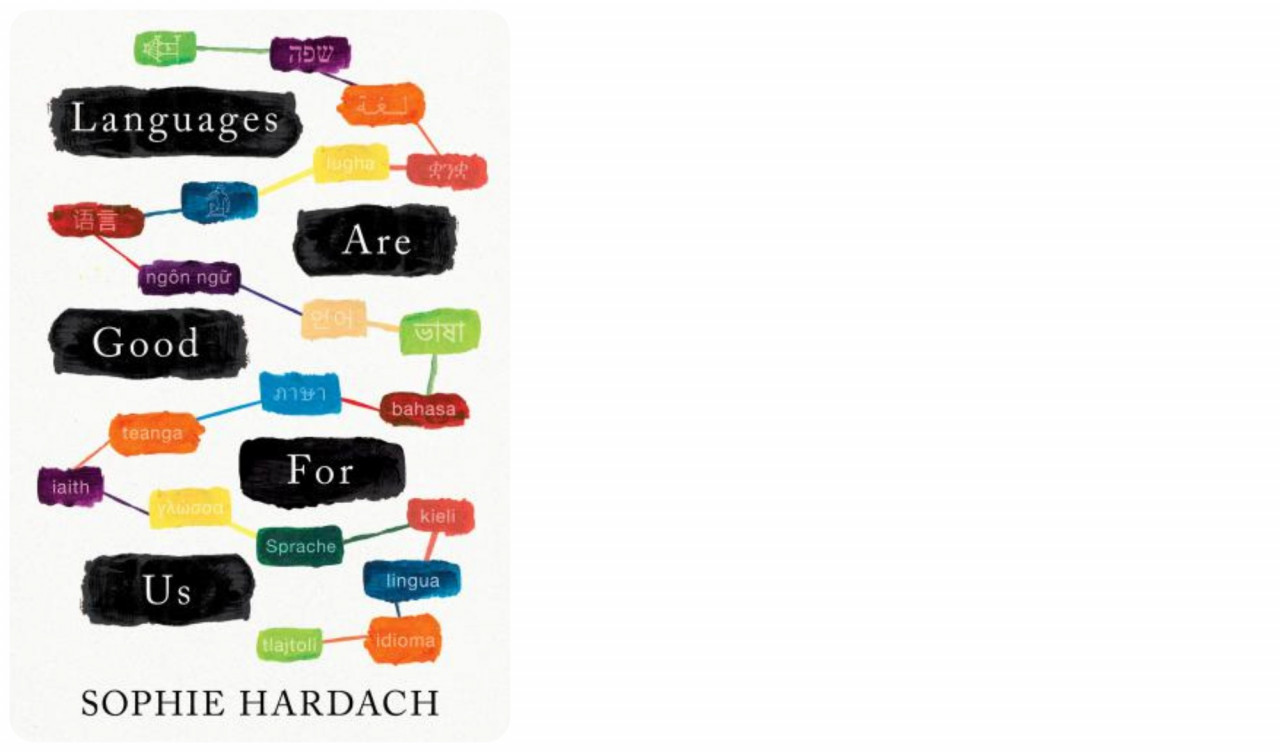

Sophie Hardach’s latest book, ‘Languages Are Good For Us’, her first work of non-fiction after three novels, is as idiosyncratic as it is passionate. While scholarly, this is not a dry academic text. There is hardly a page where the author’s exuberant enthusiasm for her chosen topic isn’t evident.

Words rarely come out of nowhere. Hardach explains two main mechanisms whereby new words come into languages. One is that the word is simply borrowed from the language of the people where a previously unknown item originates, often transformed to reflect local phonology and speech patterns, such as how in a Malaysian context ‘bus’ became ‘bas’ or ‘taxi’ became ‘teksi’.

The second mechanism is naming a new object in relation to the closest similar object. Sweet potatoes and potatoes are unrelated plants, but for English speakers, they are sufficiently similar that the adjective is simply grafted onto the better-known plant.

Both mechanisms can be seen at work with pineapples. The English word describes a fruit vaguely resembling a pine cone, with which it shares Fibonacci attributes, while elsewhere the word for the fruit is often a cognate along the lines of ‘nanas’, ‘nenas’, or ‘ananas’, derived from the original name, which along with the fruit originated in what is now Brazil.

There are many fascinating digressions in this book as the author follows words and languages through time and space. She traces the spice cumin, through etymology and trade, all the way back to Sumerian times, via its medicinal use by Hippocrates, the Greek physician who still lends his name to the Hippocratic Oath medical doctors take upon graduation, and further to a geographical divide, where west of Persia cumin is known by cognates similar to the English word and its Sumerian roots, while east of Persia the word becomes Jeera, or Zeera, or phonetically similar variants. Still in the same region, we learn that ‘bandar’, the Arabic for ‘port’, came into the language from Persian.

Elsewhere Hardach traces Star Trek’s Lieutenant Uhura’s name, back through the Swahili ‘uhuru’ (meaning ‘freedom’), via a Palmyran inscription found on a stone at a wet windswept outpost of the Roman Empire in northern England.

Almost all of what we know about ancient languages is because of writing, some of which has been successfully translated thanks to multilingual texts or inscriptions. Perhaps most famous is the case of the fabled Rosetta Stone, which bears three identical passages written in Ancient Greek, Demotic text (which bears a relation to Coptic scripts), and Egyptian hieroglyphs. This allowed archaeologists and scholars to translate and better understand the ornate pictograms left behind by the civilisation that built the Giza pyramids and more.

But though it is the best known, the Rosetta Stone was not the only polylingual text found. Throughout what is Eurocentrically defined as the Near-East, writing, some of it multilingual, has been preserved and found. Some of the more banal items – a letter requesting a table and a chair, for example, are those that often resonate most. Because of their mundanity, they are relatable. They also give us a picture of trade, and how peoples mixed their languages and cultures, and bloodlines in the distant past.

For a Malaysian reader, this sort of scene is more immediate and obvious than for say an American or English reader, since in Malaysia it is not only possible, but common to hear words from several languages used in a conversation, or even in a single sentence. But many parts of the Anglosphere have embraced monolingualism, to the extent that only speaking one language is seen as the norm, while speaking two languages or more may be perceived as the exception, or even in extreme cases as an anti-social aberration. This is further reinforced by the global dominance of English, giving even less incentive for monoglots to open their minds and hearts.

It wasn’t always this way. Indeed, it is a quite recent phenomenon. Hardach recounts that less than a thousand years ago such was the linguistic diversity in England and Wales that William the Conqueror needed 11 interpreters to compile the Domesday Book which surveyed those lands.

‘Languages Are Good For Us’ is a book about language, but it is also, somewhat surprisingly, a book about food, with the author slipping into culinary musings, often for pages at a time, whether discussing the importance of seasonality in Japanese cuisine or describing the geographic delineation of the Fish Sauce Range. There is even a cake recipe, with suggestions on how to decorate it with characters from the ancient Cypro-Minoan script.

It is this sort of idiosyncrasy that makes up a large part of this book’s not inconsiderable charm. While wide-ranging, the book doesn’t attempt to be comprehensive or systematic. Instead, it focuses more on the intriguing stories of words, language, and writing, things that are at the very root of what makes us humans such a unique and extraordinary species. – The Vibes, April 22, 2021