THE town of Papan, derived from the Malay word for plank, is located 16km south of Ipoh, in the Kinta district of Perak. As its name suggests, Papan started off as a timber outpost led predominantly by the Mandailing community. Originally from Sumatera, they played an important role in the development of Perak in the 19th and 20th centuries.

In 1876, British resident general Sir Frank Swettenham gave Raja Asal, a Mandailing chieftain who had migrated to Malaya in the 1840s, the sole right to mine tin in sites between Kinta and Belanja. Before that, the main activity in Papan was the logging of Chengal wood from Ulu Johan, upstream from Papan. It was transported downstream to Pengkalan Pegoh, a river port along the Kinta River tributary.

‘Raja Bilah & the Mandailing’s in Perak, 1857-1911’, authored by Abdur-Razzaq Lubis and Khoo Salma Nasution, states that the Chengal woodcutters were Malays, while the sawyers were Chinese. The Guan Yin temple, built in 1847, is evidence of an early Chinese settlement in the area.

Raja Asal was succeeded by his nephew Raja Bilah who took over as Penghulu of Lower Perak. He was appointed by the British as a headman and tax collector and moved to Papan from the tin-rich Belanja district. European investors were brought in during this time, including Leech, de la Croix, de Morgan and Hale. Dams were built, steam engines imported, and water-engineering techniques introduced in the tin mining industry.

Under Raja Bilah, Papan thrived as an administrative centre for tin mining activities in the Kinta Valley. He was accepted by both the Malays and the Chinese miners as the head of the town. At that time, 38,000 people, mainly Chinese tin miners, lived in Papan.

Papan survived for over a century as a mining town until the crash in tin prices in the 1980s which saw an exodus of residents to nearby towns and cities.

“The exodus from Papan is also attributed to the controversy over pollution caused by operations of the Asian Rare Earth plant near the town. This was linked to a rise in health issues amongst residents of Papan. The rare earth plant closed in 1994.”

.jpg)

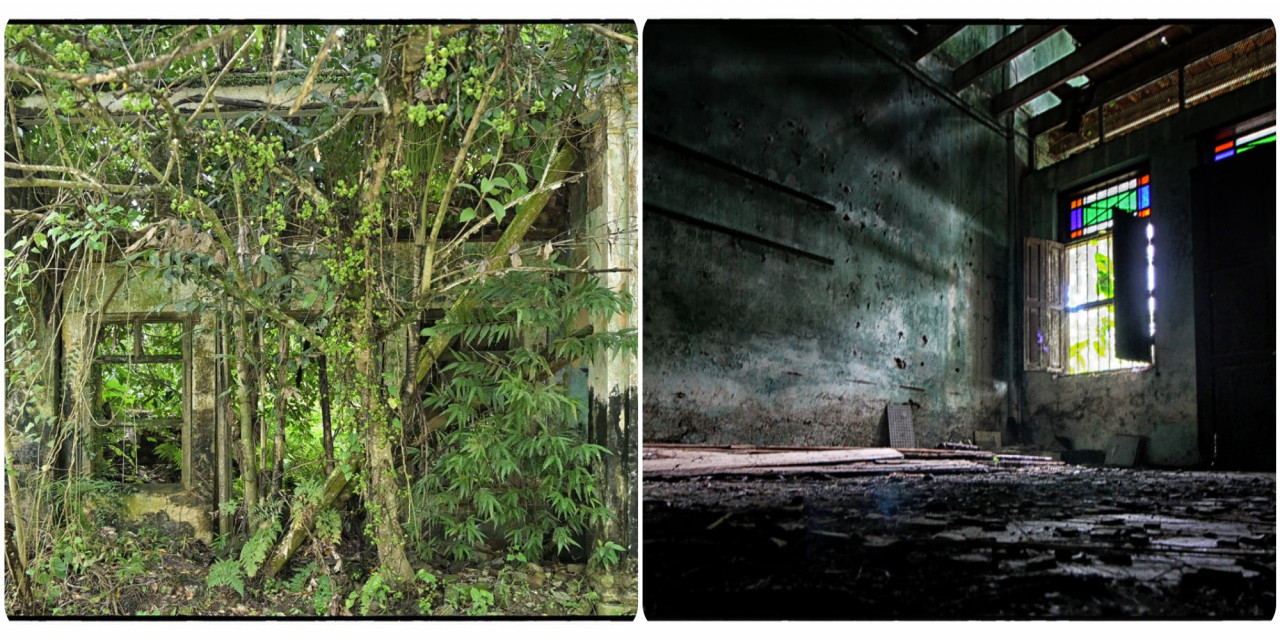

Today, nature is slowly taking over the dilapidated and unoccupied buildings in that town. And although there has been talk about gentrification of the site, there seems to be some form of appeal in the decaying town and buildings. Some premises seem to resemble scenes out of the movie ‘Lara Croft: Tomb Raider’. One expects to see Angelina Jolie (who plays Croft) swinging by while hanging onto one of the vines or roots hanging through the structures.

In some places, the overgrown roots and shoots on the mostly blue indigofera tinctoria hued walls resemble the overgrowth on ruins of the famous Wat Ta Phrom in Cambodia’s Angkor complex.

The structures in Papan town may be unsound as seen by the collapsed wooden beams and staircases. But it is still a haunt for the odd Instagrammer who happens to stumble through the one-street town on their way to other parts of Perak. However, local townsfolk are seemingly not amused by the antics and acrobatics of posers and find the intrusion a disruption to their place of solitude. Some of the decaying homes still have occupants despite the dilapidated exterior.

Ipoh-based photographer Philippe Durant has captured some scenes of the decaying town. It is now home to about 300 people who live in traditional new village-style wooden houses in a place where time seems to have stood still.

The population in Papan is an ageing one, though there is a Chinese School – SKJ (C) Papan – which has low enrolments. Just before the Covid-19 pandemic hit, a stash of old files and documents, including graduation certificates, old photos, textbook loan registry, statements, accounts, teaching reports and letters dating back to 1929 were discovered in this school. These are being processed by a team of curators and volunteers.

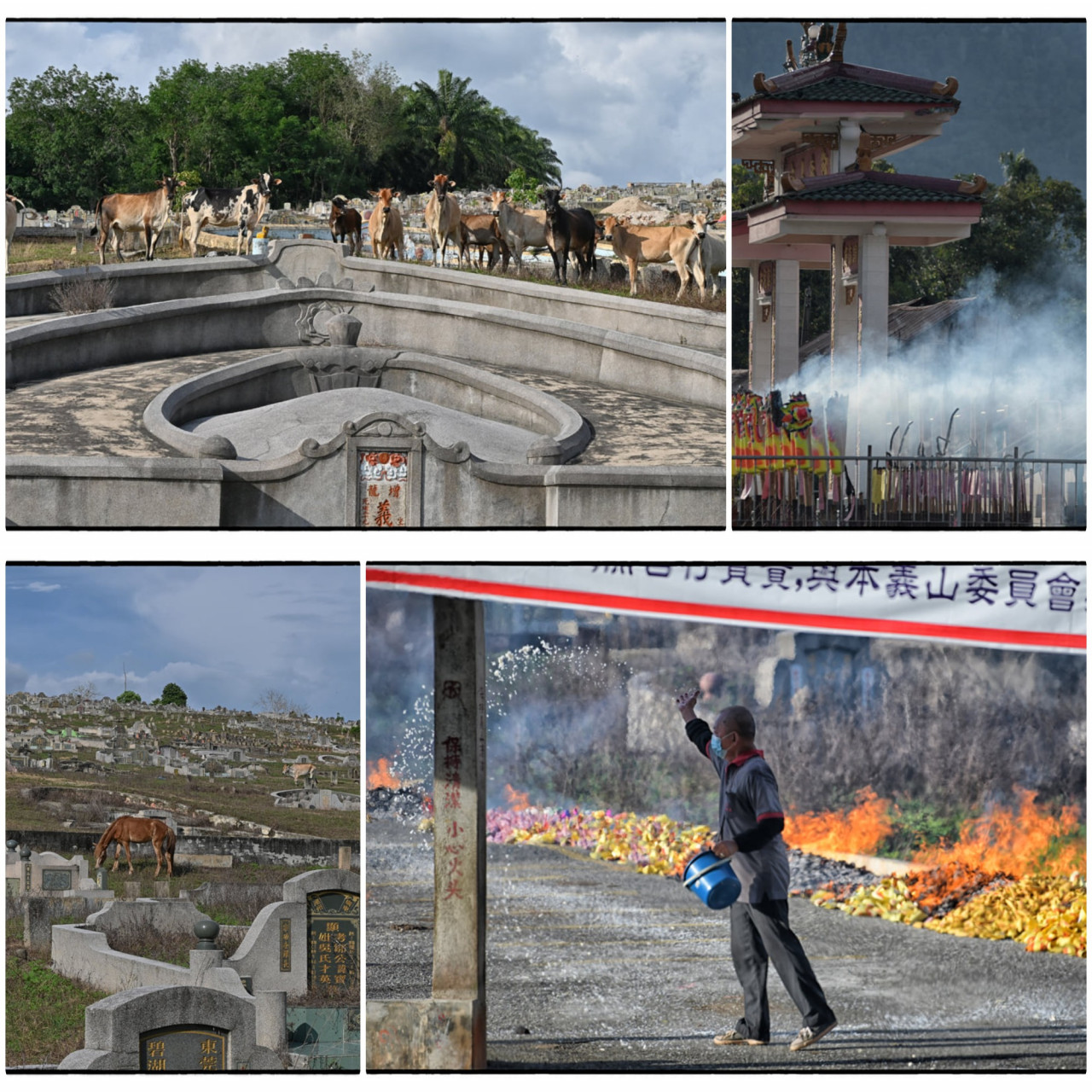

The town which is just off Jalan Lahat (between Pusing and Ipoh) is usually busy during the Chinese Cheng Beng Festival. It is akin to all soul’s day, or the day of the dead (if you have watched the animated movie 'Coco'). The cemetery and Guan Yin temples next to it are usually brightened by colourful offerings for the departed. And flames lit to burn these during this festival. However, this year the cemetery was quiet due to the recovery movement order (RMCO) in place. The only visitors for the departed seems to be a few grazing cattle and horses.

Glimpses of Papan’s glory days can be seen in its beautiful but decaying ‘straits eclectic’ design shophouses, complete with five-foot ways and beautifully designed wooden windows and doors.

Likewise, Istana Raja Bilah and the Kampung Papan Mosque feature unique Mandailing architecture. They are the tiered Juglo roof that departs from the Arab and Indian inspired dome and minaret mosque design in other parts of Malaysia. These are also in poor shape, despite the house being listed in the national heritage register by the National Heritage Department.

Time seems to have stood still in some spots like the old hair salon in Papan town that ceased operations about five years ago. But it still houses remnants of its past occupant’s tools of the trade. A barber’s chair, Pureen talcum powder and a broken clock – apt symbols of how Papan is now frozen in time.

The only surviving businesses seem to be a grocery store and two coffee shops. There the locals catch up on the latest news in town and gather for a game of mahjong – this was before the movement control order (MCO).

Papan was also the home of World War II heroine Sybil Kathigasu. She was a nurse who was tortured by Japanese soldiers for treating injured anti-Japanese guerrilla fighters and relaying information to the anti-Japanese army from banned Short Wave (SW) radios.

Sybil survived the war but succumbed to her injuries and died while seeking treatment in England. She is the only Malayan woman awarded the George Medal for Bravery. The clinic that Sybil and her husband Dr Abdon Clement Kathigasu operated from still stands in the town. It is being managed by the Perak Heritage Society.

In earlier news reports, society president Law Siak Hong had cleaned and cleared the decaying rooms in the property. He attempted to restore the clinic to its original form as best as he could. Even the hole under the stairs where Sybil is thought to have hidden her SW radios that she named ‘Josephine’ was maintained. Papan was also the setting of the famous Papan Riots between Chinese triads that were sparked off by a brothel brawl.

Suriati Ahmad and David Jones in a conference paper titled “The Importance and Significance of Heritage Conservation of the ex-tin Mining Landscape in Perak, Malaysia, the Abode of Grace” state that the tin mining industry in Malaysia has been classified as its oldest industrial heritage. Malaysia was the world's premier producer of tin, supplying some 40% of the world's tin until the late 1970s. The biggest mining areas were situated in the Larut and Kinta Valley districts (Ipoh, Gopeng, Kampar, Batu Gajah, Tronoh).

In Papan’s case, the town is being rapidly lost to decay despite its rich history. Among the ideas being bandied about to restore, or rather preserve its legacy, including plans to develop and gentrify the area and repackage the history of the town together with the eco-tourism – the nature trails along with the Papan Recreational Forest Reserve and farms in the area.

The other option would be to maintain the town and its decay – that seems to have its charm and appeal the way it is. It would tell the story of Perak and its glorious mining past, with the option of marketing Papan as an open-air museum or movie set. It could be modelled after the ghost town of Craco in Italy that has served as a production set for many movies including Mel Gibson’s ‘The Passion of The Christ’.

It is, however, imperative that the opinions of Papan residents, their descendants and property owners be sought. Papan should be viewed as a place that tells the story of the communities that thrived and worked together to make it the success story it once was – the indigenous tribes, the early Mandailing settlers (early 1800s) and the Chinese tin miners (mid-1800s).

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation (Unesco) recognises industrial heritage as a cultural landscape that demonstrates the interaction between human and nature. While the Australian ICOMOS Burra Charter (1999) describes historic mining landscapes as “places of cultural significance to enrich people’s lives, often providing a deep and inspirational sense of connection to community and landscape, to the past and to lived experiences.”

Many countries in Europe and Japan have preserved their mining heritage and outlined the significance of their mining landscape to local and global growth. There are currently 16 mining heritage sites in Unesco’s World Heritage List. They are connected to mining from various historical periods and involving a range of raw materials. Some good examples are the Cornwall and West Devon Mining Landscape, the Japanese Iwami Ginzan Silver Mine and its Cultural Landscape (both Unesco World Heritage Site), and the Sovereign Hill outdoor museum in Ballarat, Australia among many others.

In Malaysia, despite its major contribution to the early economic wealth of the country, many tin mines have been abandoned and closed. They have been converted into more profitable ventures such as housing estates, commercial and institutional centres, and agricultural and recreational areas. More often than not with little regard and acknowledgement for its history and heritage.

Maybe it is time for Malaysians or rather keepers of our history and heritage to think outside the box. Look at recognising our uniqueness and heritage that is distinctive only to the country and the people who call it home. This is instead of getting all hot under the collar when neighbours lay claim to more common and shared heritage – like hawker food.

A good place to start would be preserving the legacies of the communities and industries that contributed to the growth and wealth of the country. Like the tin mining industry – towns like Papan. – The Vibes, June 13, 2021

.jpg)