EDDIN Khoo: Judging by some responses to your book The Apple and the Tree, there appears to be an expectation that it is a validation of your father, Tun Dr Mahathir Mohamad.

The book is, in fact, about you, and more importantly, about your generation – the post-Merdeka generation.

Could you clarify these expectations by way of telling us what compelled you to write this book at this time?

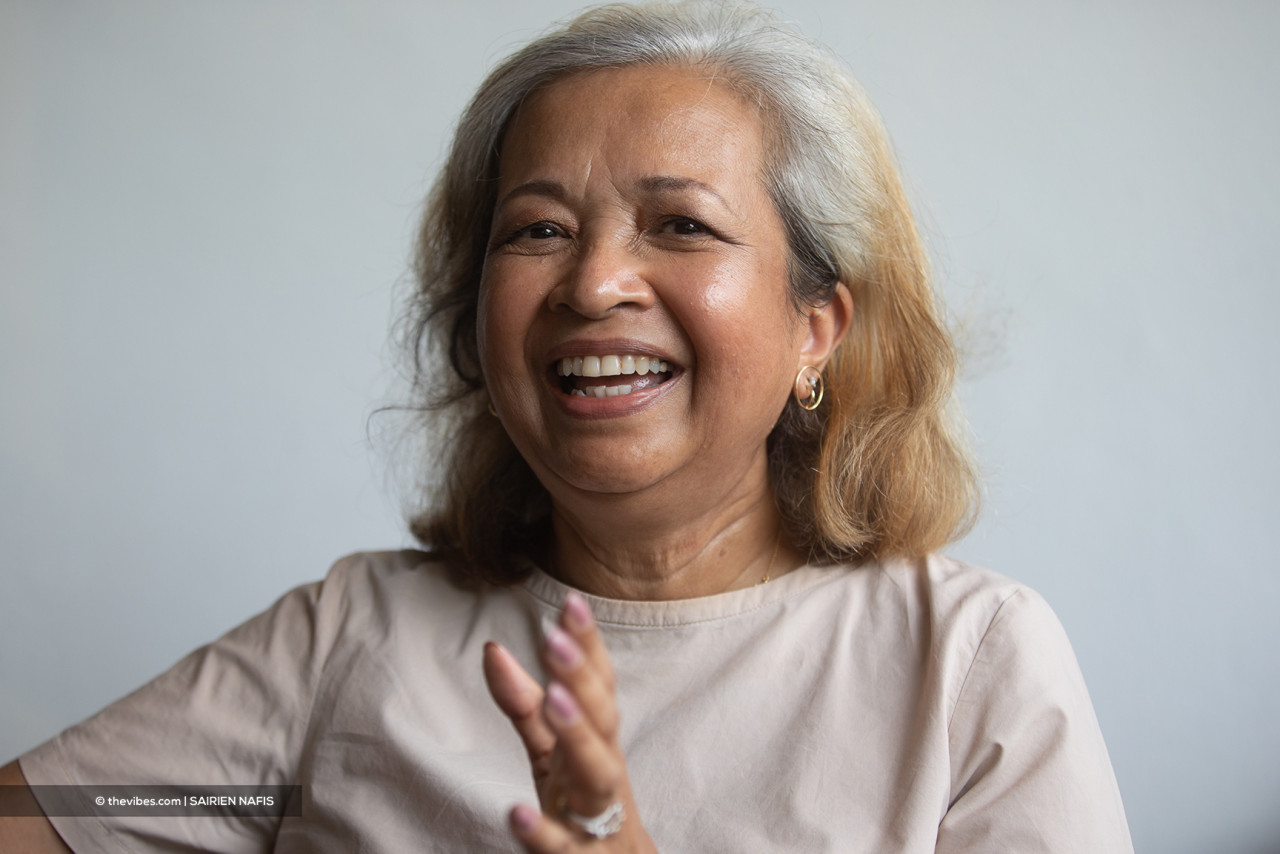

Marina Mahathir: The main motivation, really, was that I had completed a Masters in Creative Writing not so long ago, and I really didn't want the studies to go to waste. Naturally I wanted to come up with a book, but when I got back I didn't have a book deal, an agent, nothing.

But I continued writing and it so happened that a year ago Penguin SEA approached me and asked if I would write a book on exactly this topic. I already had bits and pieces and thought "why not." I had already worked on some parts for the course, and this is basically what I know. It has been said that you should always write what you know, and while this is not the only thing I know, I thought I would start with this.

It really was a whole set of circumstances that came together. Then, of course, there were the lockdowns, which allowed me simply to be able to stay home and work on the book.

I had not particularly thought I should write this book to stir things up. I just wanted to write what was close to me, which I knew quite a lot about, and that was basically it.

Quite a simple reason, really.

EK: What were your expectations about writing a particular kind of book and having to deal with a readership that is wanting, expecting even, something else?

MM: In a way, I kind of expected it: I know what the book is about, and its unfortunate that some people have been judging the book by its cover – literally – and also from the excerpts that were published, which were not even chosen by me.

From that, things were extrapolated and conclusions were made about what the whole book was about. I had already observed that on Facebook: I was doing this slow promotion of the cover (of The Apple and the Tree) and the moment I revealed my dad on the book cover people began reacting.

But, yes, the book is about me: and what helped tremendously was when I asked my publisher, "who is the main character in this book," and she replied directly, "you." And I thought that helps a great deal, because it helps me to focus.

Yes, it is also about my relationship with my dad, and yes, he is a big figure in my life and I would be silly to deny it, but it’s also so much about a struggle to be myself, to forge my own identity. And there were things that helped me along with that, particularly my work with HIV and more.

EK: The question of family is always a very emotive one, especially when you are writing it. Autobiography remains an elusive form – Tolstoy declared, ironically, that “happy families are all alike: every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way”.

How delicate was it for you to approach the subject of family, especially given Tun Dr Mahathir’s looming presence over all our lives, to ensuring that a balance between telling a truthful tale and simply appearing self-justifying was achieved?

MM: It was, I guess, kind of delicate, and you can’t possibly put everything in. You have to make choices because you also want to move the story along, and can’t be bogged down in endless detail. There is a bit where I describe our house in Alor Star, and someone remarked, "eh, that slows things down".

But I also didn't show the manuscript to any member of my family – not my husband, not my parents, no one… because I really wanted to keep the story mine, and from my point of view. My brothers, for example, would have disputed what type of car we had or something like that, but, in the end, this is my story. Yes, it's very subjective, but it is mine. If you see differently then you should write your own.

I also was careful about writing about situations I was witness to. I didn't want to write about things I only heard about partly because it would then have involved a lot of research, interviewing a lot of people, which I didn't really want to do.

I told my parents and family early on that I was writing this memoir and was greeted with total silence.

I did have my dad over one time and said "I am writing this book" and he responded, "is it about me?", and I replied “No, it is about me!” though I did, later, have to ask him about some of our family history.

EK: Did you ever feel as you were writing it that you were revealing too much, or were justifying too many things?

MM: I felt it had to be true to me, authentic and sound like me, and so if I was telling too much I suppose that means talking about flaws and weaknesses in me.

I think I did that and I think that is unusual for Malaysian memoir writers. But I was also mindful of respecting some things – people’s privacy, for one, and unless I was going to talk to these people, I pretty much left it out.

EK: I was especially moved by the first part of the memoir: you were born in the year of independence to doctor parents, working within the confines of a small town, Alor Star, also the home state of our first prime minister.

In reflecting on the early years for this book, how deeply did you have to reach to make some sense of these convergences? Did they mean anything at all?

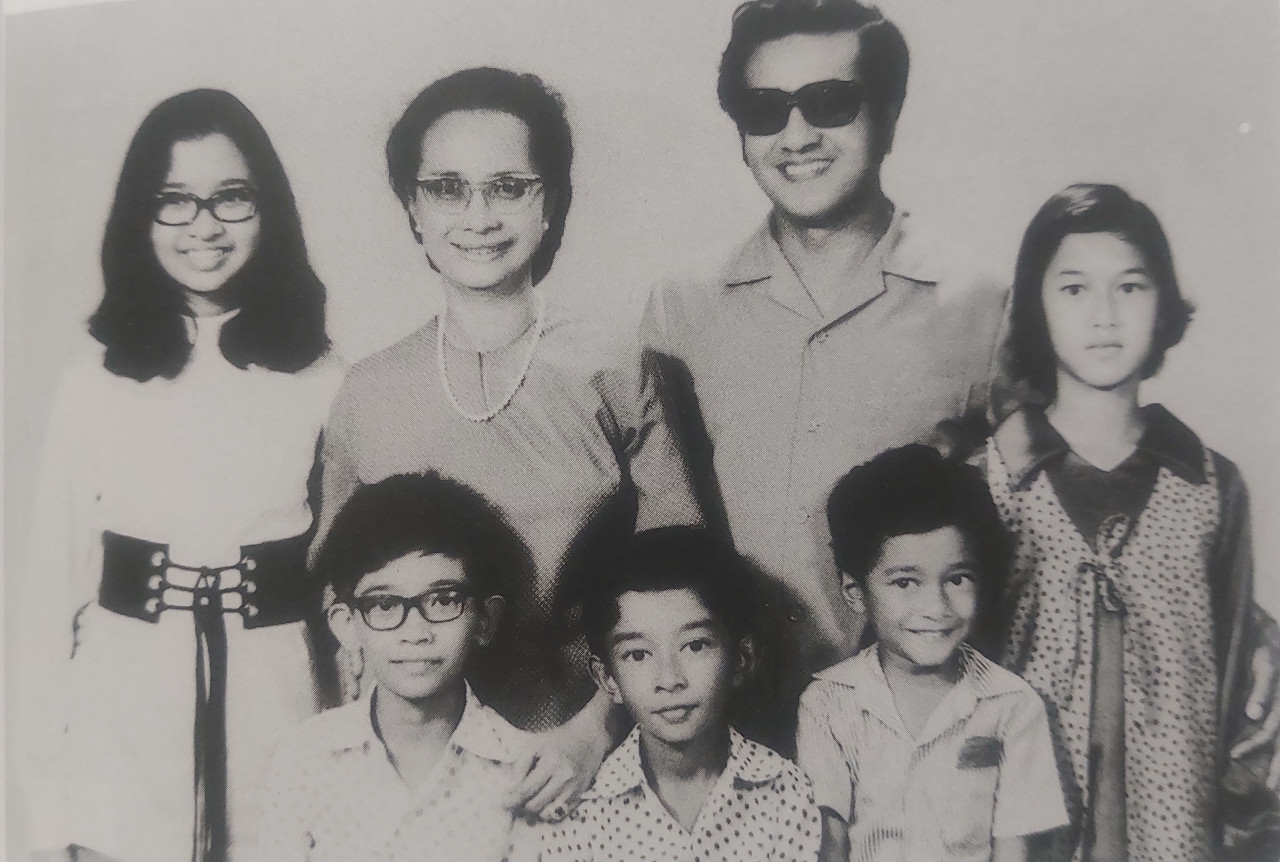

MM: I think there has always been a misconception that I grew up as a PM’s daughter, and I have to remind people that dad became PM when I was 24.

I grew up as a small-town doctor’s daughter. As he was a doctor in a small town there was some element of being well-known and all that, but ours was a pretty normal childhood, and really we never dreamed we would end up where we did.

I don't think anyone else thought so either even though dad stood for elections in 1964, lost in 1969 and then came back.

Some years ago I did something for (the Five Arts Centre’s) Marion D’ Cruz – it was a series of 2-minute plays where she gathered a few people to narrate stories. My story was called ‘K…..’

It was a story of how I went to a school reunion – I had been in Sultan Abdul Hamid College for a short while, my dad’s alma mater. At the event, we all had to get up and say what we're doing now and all that... And there was this one guy – who I had totally forgotten – who got up, laughed and started telling this story of how his father had been a classmate of my dad’s and how he then had been mine, and that both father and son had done the very same thing – which they both thought was really funny – which was to call my father and me ‘K…..’ because we had some sub-continental blood.

It was then that I sort of remembered how much he had tortured me then, and of course, at that time, neither father nor son thought that anything would become of either of us, so it was ‘okay.’ Now he thought he was trying to make up for it by telling this funny story, which I didn’t find funny at all.

Which just goes to show that you have to be nice to everyone because you never know where they’d wind up.

At one time, nobody saw this future for my father, and neither did we, the family. We were just a small town family, though undoubtedly in a nice part of town, and pretty regular people, and that was the same at home.

To this day I think, of those 22 years particularly, as a kind of a dream. Did it really happen? Obviously, it did but sometimes it is weird. Time flows and you find yourself here now, with that in the past, and it was a real past but still feels a little surreal.

EK: Politics rears its head early on in the book, when you thought your father would be arrested after he wrote that infamous open letter to Tunku Abdul Rahman. You were still a child, what kind of effect do you think it had on you about what politics and its consequences could be?

MM: In the book I recount how my parents were very protective of us. They didn't tell us very much, or explain what politics was about. As far as I knew then, politics simply meant my dad would stand for elections, enter Parliament, then go away for a couple of weeks every few months, and that was it.

I didn't know anything about machinations, or what party politics were. So when that happened I just came to the conclusion that if you displeased someone, especially someone powerful – of course I knew who the prime minster then was – it was going to lead to really bad consequences, which was frightening to an 11-year-old.

So, it was a pretty naïve view, and I add that is what made me empathise with Anwar’s kids later on – by chance one of Anwar’s daughters was the same age as my daughter and they went to school together and you know what my daughter said when she read that: “Ma, you empathise with Nurul Ilham, but you forgot about me."

And it struck me that I had done the same thing – I had failed to explain to her what that episode was about. She was the same age as I had been. And it dawned on me, that there had been a time when I too thought that politics was too grown up to explain to children.

EK: Throughout the book, you write revealingly about living under a condition you call Impostor Syndrome – a form of an "inferiority complex." You claim you “don't know where this comes from.”

Writing is obviously an exploration: having written this book, I’d then like to ask you directly – where does this come from?’

MM: Probably two things – my dad saying, when I was around 14, that I was just mediocre; and I thought ‘I am not good at anything,’ and the fact that I remember that particular instance to this day, it must have really impacted me.

The other is going to boarding school – the TKC (Tunku Kurshiah College) where I had been admitted late – there was advance notice of me coming, and I always had this feeling that though I was qualified, there were a lot of girls there – TKC was very merit based, they creamed off the smartest girls – who thought I didn't deserve to be there, that I got there because of the name, and that weighed heavily on me.

Someone there actually said to me, “Marina, I was so worried for you.” Did you think I was going to fail? I had to contend with that all the time, and I still had to contend with that later in life, in adulthood, in whatever I did, and it is very hard to shake off.

What kind of saved me was going into HIV AIDS (advocacy), finding my own path and gaining confidence, but even then I always feel that everyone is so much smarter than me.

And it’s not about being falsely humble, I really do feel that.

EK: How does the act of writing a book like this change that?

MM: The one thing I am a little confident about is that I can write. I have been writing for a long time, though writing very differently, and I have learned to write differently on my MA course. What I would really like is for people to say, 'you write really well'. I don't care if people disagree with me but say 'actually she writes really well.' Then I would be thrilled.

EK: But before you entered into women’s activism and HIV you were a writer – you entered journalism in the NST at a crucial time in the country’s development, you have maintained a column in The Star for years and years…

MM: When I was writing the column people would say, “you write very well…” That was fine. But when I went to do this course I just really had to up my game. It was quite unnerving because, one, I was among the oldest in the class, and secondly, my education. I was a science student so I didn't really have any classes on literature. That side of things had to be on my own.

When I attended the program I found all these people who could talk about books just like that; the way they thought, the questions they asked, how they commented, from angles I never thought of. I tended to read books and kind of accept them for what they were, and I thought we really were not taught critical thinking. I realised this is what is really damaging our society.

EK: Let me now enter the territory of Dr M – we are still very hung up with the Merdeka generation, your story is very much about the post-Merdeka generation, one of greater opportunity, greater social mobility. The ‘mobility’ of this generation was refracted in the rise of Tun Mahathir within our political structure.

Having a very close personal relationship with him – although descriptions of him appear very formal, not unapproachable necessarily, but rather patriarchal – how much was it a challenge for you to distance yourself, observe from a distance, distinguish the personal from how he is perceived nationally?

MM: I didn't consult anyone except for historical facts, and I certainly didn't consult my dad. I think he might have had a niggling worry about what I was going to say. Over the years there were many matters on which we didn't agree, though not publicly. We’ve never attacked each other publicly – I don't think that is right. It’s not the way to do things.

In the book, I try to keep things at the micro level as much as possible so that it is about my personal relationship. So he as dad, rather than he as PM, though I will admit sometimes it’s hard to differentiate the two, because he has an effect on policies and things I work on – AIDS, for example.

I wouldn’t say it was easy but I think I solved it by keeping things close to me, and just writing away on my own. I was very afraid that what would happen if I consulted him was that I would take in his version of things. I didn't want to do that because the book had to be about the way I saw things, and it was very clear that I wasn't writing a hagiography.

It is just the way I saw things and the way things unfolded in my life. I know one of the things you pointed out was that I gave very sketchy details of national events – that's partly because there is already so much written about that, and I am not academic enough to go and want to analyse everything and give my idea.

Two, I was very clear that I really didn’t want to talk about things that I was not actually witness to. For instance, about Anwar and the accusations (surrounding the events of 1998) – I talk about how I watched it on TV and turned to my dad and said, “Is this all necessary?”. That was the truth… So yes it is a memoir, a personal memoir, it's not reportage… That has been done.

EK: When you do talk about points of disagreement between you in the book it is described in terse terms, and then the conversation is over. There is an instance when he uses the word ‘liberal’ in a disparaging tone, yet he is a very liberal man in many ways. What is the nature of your disagreement, really – is it generational?

MM: I think there is a lot that is generational – he is of the pre-Merdeka-war generation. I am post-Merdeka. Also, our educational exposure was different. There is a difference between going to Singapore to study medicine – a Singapore that was such a part of us – and me going to the UK and the US. That he sent me to widen my horizons and which I think he regretted and regrets to this day because he felt I came back a changed person, but what do you expect?

Yet, exposure is one thing but what brings you back to yourself and your center is the values, ethics you were brought up with. And I think, despite the exposure and all, in the end, you will come back to what you were brought up with. Your values matter – about truth-telling, being fair to people, about your family, these ground you in the end.

This ‘liberal’ label – I am not a politician so I don't make calculations based on political considerations…

EK: Does he?

MM: I think in the end he is a politician…

EK: It appears a contradiction since Tun Mahathir was very much supportive of your mother, Tun Siti Hasmah, in her work and her sense of independence, yet thinking, on the other hand, that you perhaps had too much independence…

MM: Yes. That is always the dilemma for parents, I guess. You want to let your children fly their path, yet at the same time want to keep some strings attached and haul them back.

My dad and mum have a very interesting relationship, very ahead of their time. He married an extraordinary woman who came from an extraordinary family. He never stopped her in her career; she worked all the way till she retired. And he has always been supportive of women – his chief of staff is a woman – and he always talked admiringly about the women who worked with him in various posts, so it's not an issue about getting ahead, but about toeing a particular cultural line, I guess.

And did all the right things in between, for me I guess, it’s almost like I could not really help it, because of the education I got, and the exposure, all these people I was able to meet and talk to, and all that. It just was very different, especially when I was working in HIV AIDS and I was hanging out with drug users and sex workers and all that, and seeing them as human beings who didn't have the voice and felt that I was called to be the conduit, so what could I do? I was told to be truthful so I am not going to be... I was brought up to be truthful so I can't say that these things were not happening.

EK: 22 critical years, and then a few the second time around, do you think it is even possible to distinguish the personal from the public with him (Dr Mahathir)?

MM: It is not easy. Because obviously what he does publicly – policies, laws – affects me personally. Just as an example – and I don't think I put this in the book – one of the things I think he didn't quite get… and I must say I didn't push him even though it affected me… is the matter of women not being able to pass their citizenship to their children if they are born abroad. I have a child who was born abroad and my daughter doesn't have Malaysian citizenship – that's the Constitution.

At that time there was not that loud a voice from mothers. There probably weren’t as many, but with globalisation there are more (mothers) and they are much more proactive about it.

I think life in relation to law making and policies is a lot wider: we are all learning now, everywhere in the world, that in very simple nuts and bolts politics, there is great impact, and you have to think hard about this impact on ordinary lives.

I wish our politicians talked more to the rest of us. A lot of us work on the ground, we know the actual problems and they (the politicians) seem very removed from it. My dad always says “you always tell me bad things” and I reply, “Yes, because the people around you only tell you the good things. You need someone to provide balance.”

I think he finds it difficult to hear it from me because he thinks I’m saying things just to rile him up… Maybe he’d accept it more if it came from someone else.

It's a struggle, and I think it’s not just with him, it's a lot of politicians, and on both sides. Even during the Pakatan years, talking to some of the people there, it was hard to talk about real stuff.

EK: You don't enter the political fray but when you reflect on the period of Reformasi and later the tensions within Pakatan is there a point when you rationalise to yourself, ‘my father has to fight a political fight. If besieged he has to fight back…’

MM: Well, I know that his philosophy always is ‘when people don't want me I will step down.’ That is why he stepped down at his height in 2003. Things had gotten better after the Asian financial crisis, and he felt he could now go off while at the top.

I guess in the same when Bersatu treated him in that way, he said he would go. He will fight for policies as long as he has support but once he feels he doesn't, he will stop.

From a daughter’s point of view, it is always ‘what is the source of this fight?’ If it is going to stress you out, affect your health, affect mum, what is the point of that?

But I don't think we have much say…

EK: Are you protective of him?

MM: Well, daughters are protective, but I would like to think I am somewhere in between, trying to find some sort of balance while also maintaining myself as my own self.

I am protective of him as my father, I think all children would be. I think of his health, I think of my mum and the toll things take on her, but when it comes to politics he can take care of himself. He is well adept in that and I can’t really do much for him.

EK: Many would look for insights into your relationship with your father in The Apple and the Tree, but so much is also written, intimately, about your relationship with your mother, who comes across as a stabilising factor in the family dynamic.

We often live through such a family dynamic without really appreciating it: how did you go about giving a written account of, even intellectualising, your parents’ relationship?

MM: When we were young my mother was the enforcer, but obviously – and I think this is true of every mother-daughter relationship – is that when you grow up and have your own children then you sympathise more with your own mother. I was not an easy teenager, not an easy young adult and I always actually felt, with my dad, that I had to always keep pushing, always wanting my father's approval. It's a constant struggle of wanting to be what he wants me to be, but also wanting to be myself.

But with my mum, my mum evolved from being the enforcer to being the mediator.

With her own achievements, and how much she is loved by everyone – I think people underestimate her powers of observation and what she sees in people. She is actually very sharp, though she does all these ‘perfect wife’ things, she actually does see things and observes what is going on, and when she feels the need, she will say something.

With me, in particular, she has become a conduit for me passing on messages to my dad. Because I know she will understand the human side of things, whereas he is kind of ‘up there.’

Sometimes I feel there are all these people coming to tell him things, and not accurately necessarily, about me, and sometimes he will dispatch her to ask – "what did she say, what did she do". Then I will explain things to her and she will hopefully go back and convey matters properly to him.

She (Tun Siti Hasmah) really is very strong: in some ways, much stronger than he is. Even now when she can’t see very well and her knees aren’t always very good all she thinks of is "I have to take care of him," "I got to be where he is so I can take care of him". And I try and say to him, "think of her a little." But there are some things where she really does put her foot down.

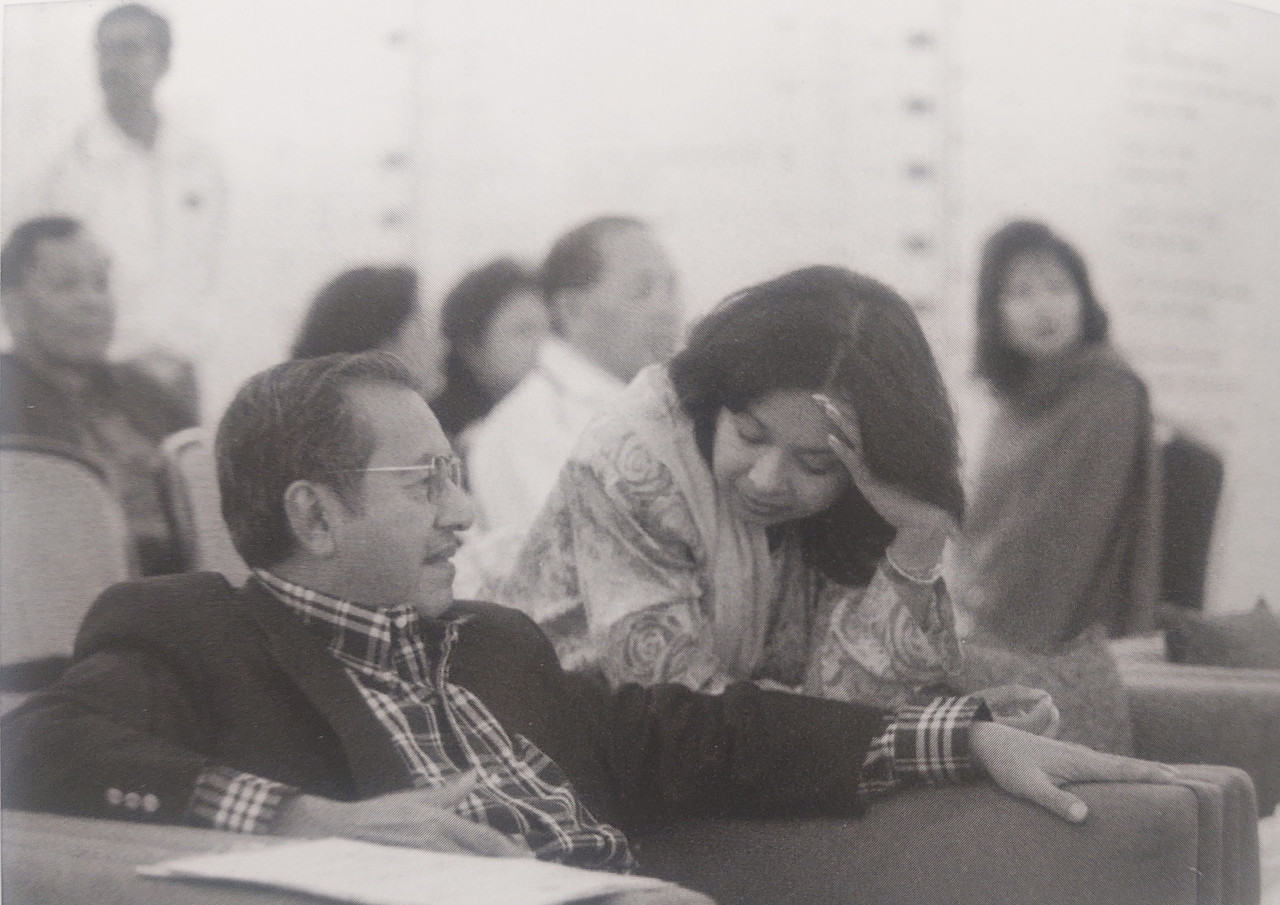

EK: One of the things I was very drawn to in the book were personal relationships that turned political, then bitterly personal again. I refer here more to the period of Reformasi than to events surrounding the Sheraton Move. It was the most challenging time for the country, your father, for Anwar Ibrahim and his family.

Can you explain, since you were so close to events, what happens when close relationships turn bitter as a result of politics? How do you deal with that?

MM: It was very, very difficult. Most of my friends are actually on ‘that side.’ I don't seem to hang out with BN types very much, partly because a lot of my friends are in NGOs and we share a common position on things, but in terms of politics, they tended to be with the opposition.

So it was tough, and I really had to rely on people who knew me well and trusted me as a person. I had to just trust my own friends and am eternally grateful they never abandoned me, even if they disagreed, and to this day one of my best friends still thinks Anwar (Ibrahim) should be PM.

I think they have also seen me speak out about human rights, about those who are marginalised, and I think I have developed that sort of capital, based on my work, what I have spoken for and what I write.

I have friends across the spectrum – most of them are what you would call the Pakatan crowd, and because our values are the same ultimately that's what matters.

So I don't care so much about people screaming at me because I don't know them and they don't me. For some people, it seems everything I have done up to this point is erased – they are cancelling me – because of what they think I did, or said, or wrote.

EK: There is a part in the book when your father is taken to the National Heart Institute for his first bypass. He gives you a letter for Anwar in the event… You still haven’t opened that letter… The Mahathir-Anwar relationship was not an ordinary political relationship: it was not a Mahathir-Musa relationship, it was not a Mahathir-Ghafar relationship, the bond was very close.

When this rupture happened, what was the emotional toll on your father?

MM: I think it was a big toll. For one thing – when the initial rumours began circulating, he dismissed them. My father is like that – he doesn't like gossip, he doesn't like rumours, he has to be shown proof. For the longest time people were whispering things to him, and he just refused to believe it – this was his blue-eyed boy. This was the position he took until the police got involved, and then…

It was like a sense of betrayal. I talk (in the book) about my sense of betrayal with some people I was very close to. I guess it was that too, for him – that someone he mentored and nurtured would turn against him. I think that was hard to accept, but once he did he decided that he couldn’t have such a person in the government and that was it – that framed his thinking.

I think I would have gone about it differently, as I say in the book, "Is this necessary?" I think there are other ways of approaching it.

What happened of course had many repercussions, including in the work I did. It is still being lived out today, but I also make the point that sometimes we see things in ways that are so black and white. I made the point that Anwar is not an ally of sexual minorities, so the people who were rightfully angry about this type of thing used against him – and which has since been also used later on – it’s not that they were standing up for the rights of sexual minorities, it was because of politics.

The point being of course that it is because it’s so stigmatised, that is why it’s being used. To me, that's not on. So many people are harmed as a consequence. These political figures, they can deal with it themselves because they are dealing with it on a political level. But the harm it causes to people who really don't have that power, for me, I am more concerned about that.

EK: There is this perception that Dr Mahathir is a logician and in that sense quite cold: is that true?

MM: Yes, he is very logical, and I think I inherited some of that… But he does have an emotional side, and that sometimes colours his view of things. He is extremely loyal to people who work for him and sometimes it is hard to try and tell him that his loyalty can be one sided.

EK: In the book, you don't deal with politics directly but there is a part that touches on the breakup of Pakatan – there is a scene where (Datuk Seri) Anwar (Ibrahim) has come to see your father to dissuade him from resigning. He encounters your brother and yourself, and he puts his head on your brother’s shoulder and says, “I tried my best.”

What was the emotional reconciliation like – not so much between Tun and Anwar – but for your family, after two decades?

MM: In the beginning – I think it was helped a lot by the fact that Anwar was still in jail. My father is a realist and very practical, and he realised that in order to get rid of Najib they had to come together.

For the older figures – Kit Siang, and others – despite being on opposite sides for so long, they have a sort of generational respect, so it wasn't so difficult.

I don't quite know who initiated the reaching out and all that, but I do know that one time he (Tun Mahathir) invited Ambiga (Sreenevasen) and Maria (Abdullah) to lunch, so he understood what Bersih was all about. I thought that was just awesome. All of them were simply being practical.

I think it helped that Anwar was not directly involved at this time. Wan Azizah was there talking on his behalf. I don't think it was easy for them – the DAP and PKR, in particular – because their membership had issues. But they all realised there were points they could meet on, and when the citizens' declaration was announced and they were all on the same stage for the first time, as equals who could actually listen to each other, and their followers could listen to each other, I realised that this was great, this is what we want and, in a way, this was a unity government in the making.

Later on, it was a case of shooting themselves in the foot. Before PH, few really trusted the opposition: they had run a few states maybe, but they hadn't run a national government. My dad being there reassured a lot of people – he knows how it works. It reassured people enough to vote them (PH) in.

And then he discovered he had to deal with amateurs who didn't know how government works, who didn't understand optics and how important this is, and who didn't understand the repercussions of policies you put out and how people interpret it. In addition, there was the then opposition who were not at all contrite, who felt they were robbed, and were determined to get it back in the worst way possible…

EK: Your social activism is well known, a very transformative experience, and described in some detail in the book: after all these decades, how far have these efforts had an impact on our social progress.

MM: Unfortunately, our social media landscape is so informed by politics and the political view of things that it overshadows what the ordinary person thinks. I think the general public is not really bothered by our diversity. A lot of the time it doesn't really affect them; on the other hand, we are being told this is how we have to think. And for some people, it does translate into action.

I do think the weakest and most vulnerable people are always going to be vulnerable to violence – women, LGBT, trans people, drug users. We have a hierarchical view of society – I am superior to you, who is superior to you, who is... we haven’t escaped that feudal thing.

I have more hope in the young because they are more exposed, they do realise we are diverse and that they are a part of that diversity. There is still a lot to be done to expand that view about young people, but they are the hope.

Meanwhile, it is really tough, you are against this huge juggernaut of painting ‘this is what Malaysia is supposed to be’ and it is a very narrow, almost entirely male view. I really think we should have more women leaders.

EK: You say you have always had this anxiety about being a writer – how does this effort reassure?

MM: I guess it is people’s responses I am looking for.

I really had to learn a lot when I went to university. I am so used to writing short columns, and the idea of expanding takes an incredible amount of discipline and learning about structure.

My structural editor made me put connector paragraphs to situate each section in a time and place, and that allowed it to flow a lot better. I did an online memoir class, chapters were workshopped in class and I did give a few people chapters to read for feedback.

I realise that we all need feedback: it was the hardest thing for me at first – I was scared of being eviscerated, but I soon realised it’s really helpful. You can’t see things when you yourself are just writing it. You do need someone else to look at it, and that's how I managed to put it in this type of structure. Sometimes it does go back and forth, it’s not so strict – I am born and here I am at this age. – The Vibes, December 19, 2021

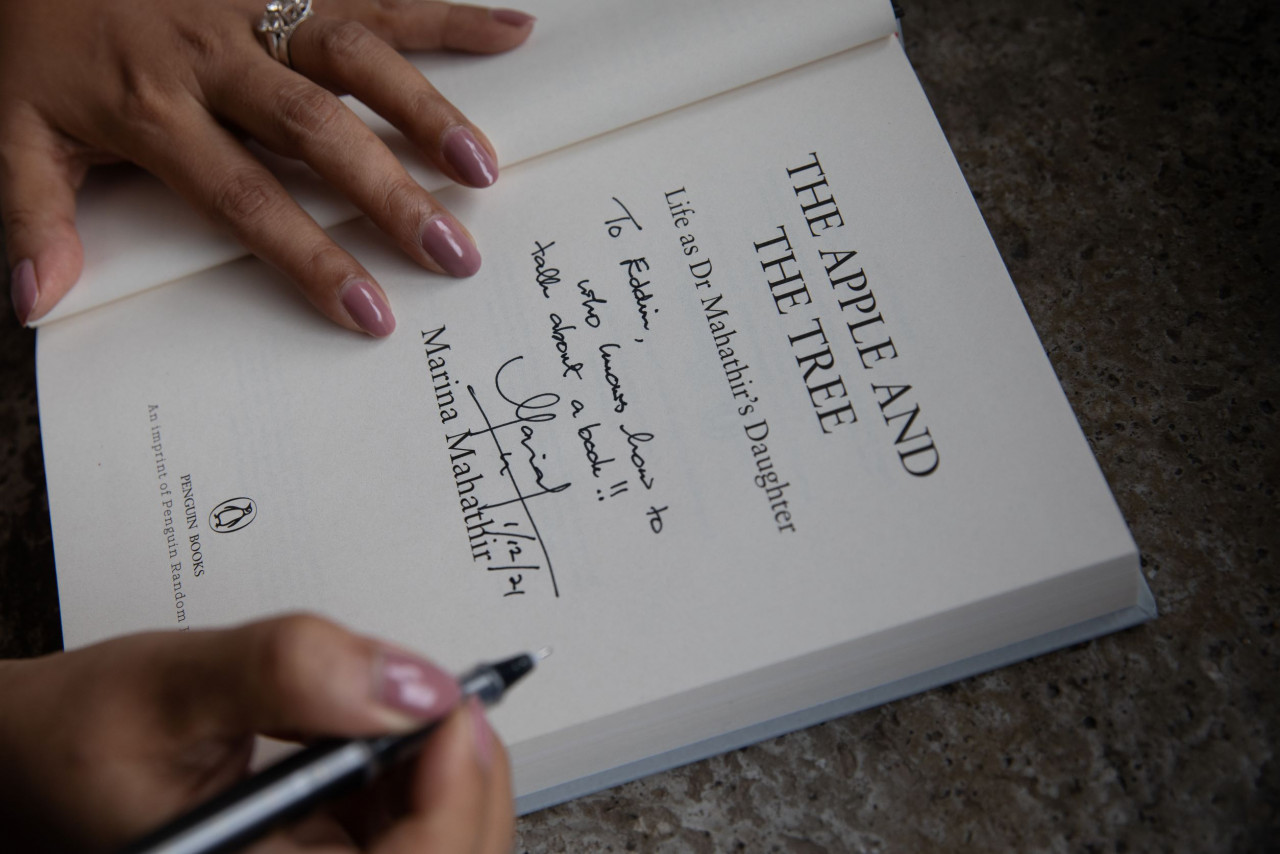

The Apple and The Tree by Marina Mahathir is published by Penguin Southeast Asia and is available at leading bookstores nationwide.

.jpg)