THE great pacific garbage patch along with distressing videos of marine animals entangled or suffocated by plastic waste have become iconic symbols of the global plastic problem. It is estimated that more than one million marine animals are killed by plastic pollution annually, while as much as 100kg of marine litter has been recovered from the stomach of a single sperm whale.

We are living in what has been referred to as the ‘plastic age’. It is almost impossible to escape from this cheap, versatile and durable material. Many of our clothes contain plastics, our food comes wrapped in it, and many – if not most – disposable products we use on a daily basis are made from some form of plastic. The global Covid-19 pandemic has seen production and use and billions of disposable face masks, and there is concern among health and environmental scientists about the human and ecological risks of microplastics that can be inhaled from these masks, or which are released by them if they are not disposed of carefully. Dealing with plastic waste has become one of the most pressing global challenges facing mankind.

Plastic is a synthetic, man-made material that can be easily shaped when soft and, once hard, retains its desired shape. Owing to its durability and versatility, plastic has replaced many traditional materials in the automotive, packaging and textile industries. Unfortunately, the generation of plastic waste has kept pace with its use, and so the waste problem has also increased dramatically over recent decades.

Trends in plastic production and recycling

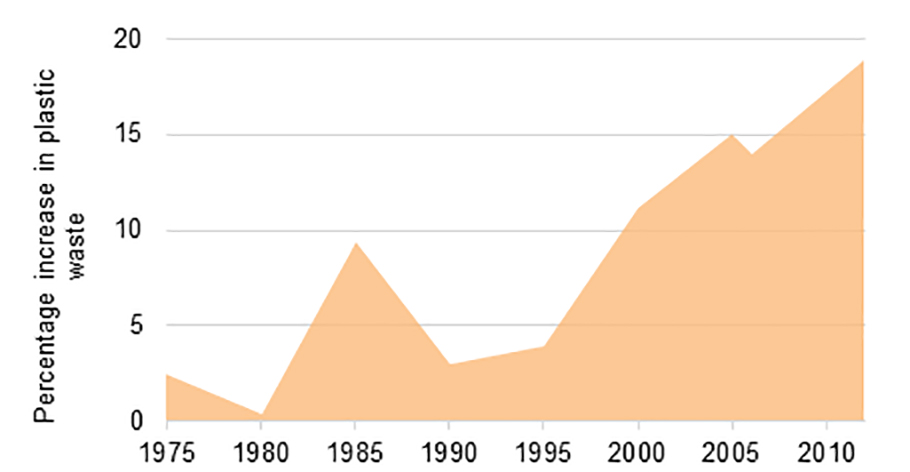

It has been estimated that, if current trends in production and use continue, there will be 12,000 million metric tonnes of plastic waste on Earth by 2050. Malaysia is one of the world’s largest producers of plastic, and is increasing its share of production (Fig. 1). This, along with imports, is putting a strain on Malaysia’s waste management systems.

Due to the low domestic recycling rates in the country, Malaysia has been importing plastic waste from other countries to produce recycled products. However, the narrative of importing waste for the purposes of plastic production shifted, when China, the world’s largest plastic importer, put a ban on the import of plastic waste. The ban caused a rise of plastic waste imports in many Southeast Asian countries. Since 2017, Malaysia has held the crown of the world’s largest plastic waste importer.

Plastic recycling is often proposed as the panacea to the plastic waste problem, both globally and in Malaysia. However, the versatility of plastics has allowed a great variety of plastic products to be produced, complicating the waste management process. Each type of plastic has its own constituents and characteristics, and this makes plastic recycling complex and costly as well as time- and energy-consuming.

Currently there are three types of plastic commonly recycled in Malaysia: polyethylene terephthalate (PET), high-density polyethylene (HDPE), and polypropylene (PP)). Very low commodity prices for recycled plastics discourages recycling. Lack of awareness among the public of proper recycling practices means that much material is soiled before reaching recycling plants; this complicates the process and acts as a further disincentive. While industrial plastic waste is easier to recycle due to their more homogenous and clean composition. However, for plastic manufacturing processes, cheaper and higher quality virgin plastic pellets are still preferred over their recycled counterparts.

Overall, it is clear there are a number of barriers to recycling, and as a result relatively little plastic is recycled in Malaysia. Even worse, the business of importing global plastic waste has given rise to illegal burning and disposal of plastic waste, further impacting Malaysia’s environment and straining its waste management systems.

Waste management in Malaysia

When plastics reach the end of their useful life they are either discarded and sent to landfill or incineration plants, or recycled and remoulded into new products. In Malaysia, 85% of waste is sent to landfill, as this is the cheapest form of solid waste management (Fig. 2). However, this process poses a threat to the environment because plastics do not degrade completely when buried in landfills. Unlike food or paper wastes which degrade, plastic waste breaks down into smaller plastic fragments. The small fragments – commonly known as microplastics – can leach out from landfill in water, and contaminate local watercourses. Microplastics pose a rather different, more insidious threat than large, whole pieces of plastic waste, because they can be ingested. We are only now beginning to realise the magnitude of the global microplastics waste problem and the human health and ecological threat it poses (Pang et al., 2021). Despite these problems, landfilling remains the preferred form of solid waste management in Malaysia. The additional problem is of course, that much plastic is not disposed of properly, and instead litters our streets, rivers and oceans.

In an effort to encourage the recycling of plastic waste, the government of Malaysia initiated the National Recycling Programme and the National Recycling Day, successfully increasing awareness of the importance of recycling amongst the public. Additionally, a mandatory separation of household waste Act was introduced in 2007. However, no proper facilities have been put in place to support the mandatory waste separation, and proper dissemination of information regarding the Act has been neglected. Participation of the public in recycling has yet to be seen due to the hesitancy of several state governments in ratifying the act for mandatory household waste separation. Despite ongoing efforts, waste recovery remained at a mere 3%-5%.

What can be done

Stronger enforcement of policy and legislation is needed to help mainstream the recycling of plastic waste in Malaysia. Stricter waste separation at source needs to be implemented, and uniform legislation across all municipalities and states need to be achieved. The government should also increase the number of recycling facilities, including waste bins and recycling centres to facilitate necessary waste separation at source. More effort is also required to promote environmental awareness and the urgency of proper waste management attitudes among the public through educational campaigns.

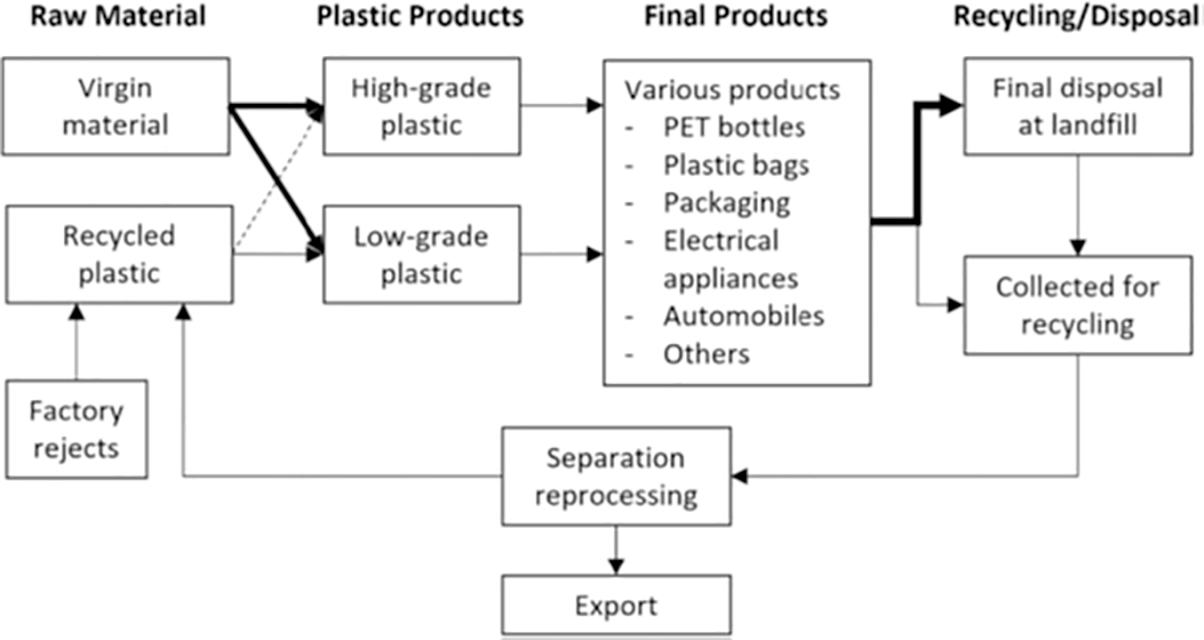

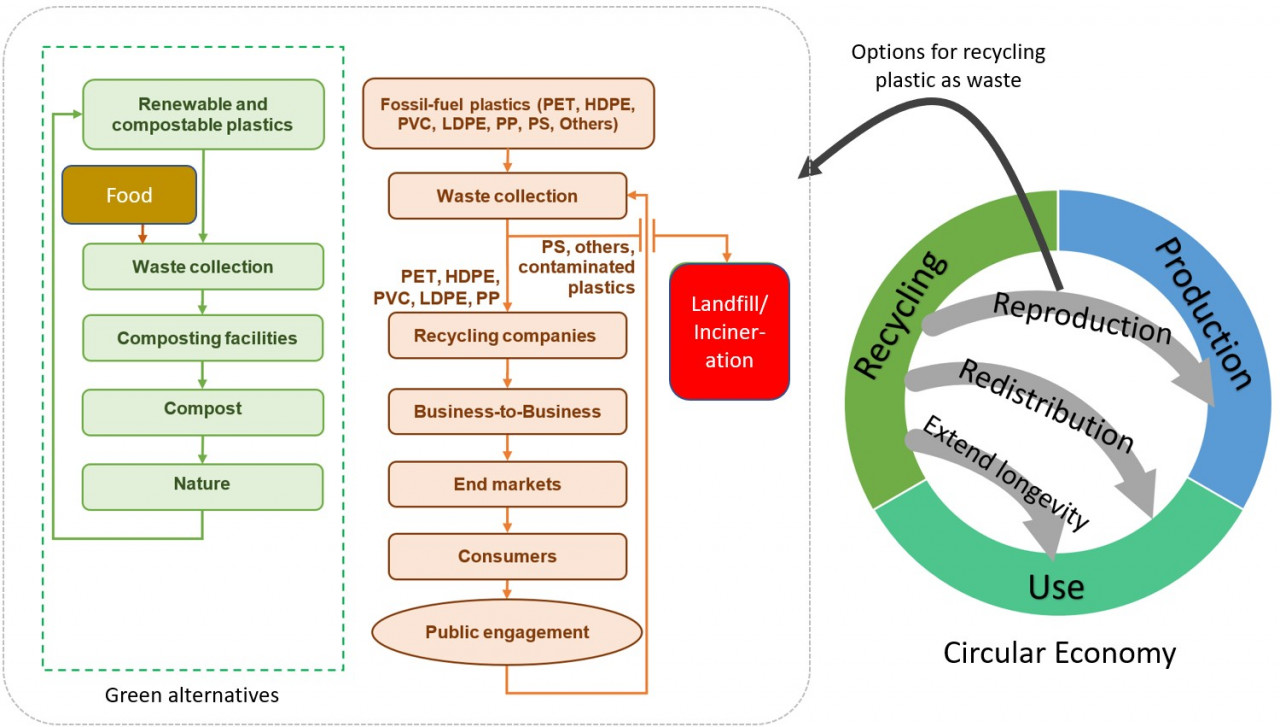

Meanwhile, to address other aspects of plastic waste problems, a green supply chain utilising a circular economy model as shown in Figure 3 should be established. In contrast to the ‘take-make-waste’ linear model, a circular economy model encompasses the continual use of resources, thus eliminating or minimising waste. This is achievable via a regenerative design and connection of supply chains for durability, reusing, remanufacturing and recycling so the product or material is circulating in the economy rather than being lost.

As shown in Figure 3, the model focuses on two aspects – the first being the current and future focus of the design of compostable or renewable plastics which is a green alternative to fossil fuel-derived plastics. Ideally, these ‘green’ plastics after their usage, can be treated along with food waste via biological means such as composting to produce compost which returns to nature. These renewable materials are thus termed as biological nutrients.

The second aspect being the solution to the current fossil fuel-produced plastic waste problems. There needs to be a systematic approach to collect, sort and recycle these plastics to produce new secondary products. Due to its closed-loop nature, these plastics are termed as technical nutrients, as they are reused in the production process. The use of decentralised material recycling facilities (MRF), such as replication and expansion of the E-idaman MRF to collect, sort and send the recyclables to recycling and manufacturing companies could potentially aid the systematic establishment of more plastic waste supply chains.

For a circular economy approach to be successful, there are undeniably many challenges to overcome, especially the difficulties in collecting and sorting out the mixed recyclables, and the poor quality of the recycled products due to contamination. To be able to regenerate waste into biological and technical nutrients, the circular plastic management model would require a collaborative effort from all stakeholders, from government on policies and regulation, councils on post-consumer collection, individuals on sorting and recycling of plastic wastes, the manufacturing companies on separation and utilising recycle materials, to innovators responsible for renewable, compostable or easily-recyclable plastic products. This would require a radical overhaul in how governments, consumers and producers produce, consume, utilise and manage plastics across its lifecycle. – The Vibes, July 8, 202

Hui Ling Chen, Tapan Kumar Nath, Chris Gibbins and Alex M. Lechner are with the School of Environmental and Geographical Sciences, University of Nottingham Malaysia; Siewhui Chong is with the Department of Chemical and Environmental Engineering, University of Nottingham Malaysia; and Vernon Foo is from CM ECO

.jpeg)