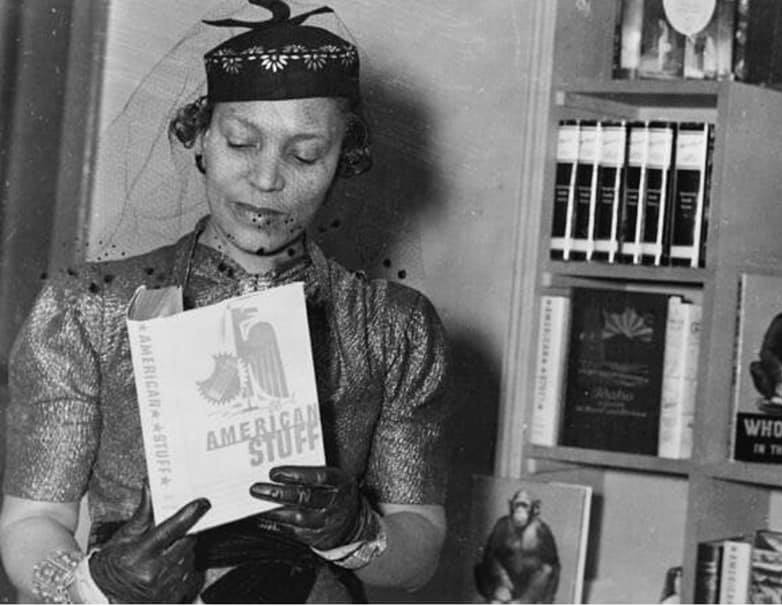

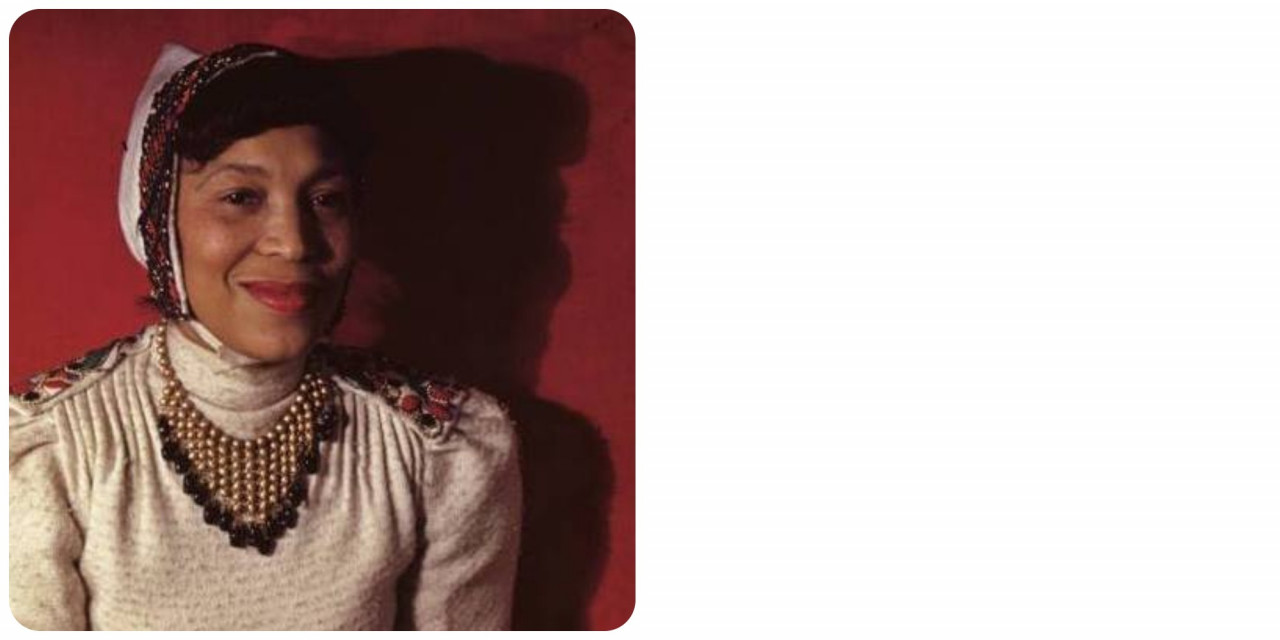

“No, I do not weep at the world – I am too busy sharpening my oyster knife.”

~ Zora Neale Hurston

IN the summer of 1927, at the Gulf, Mobile and Ohio railroad station in Alabama, the writer and folklorist Zora Neale Hurston ran into the poet Langston Hughes. Zora was in town to interview Cudjo Lewis, one of the last survivors of the Atlantic slave trade. Langston was in the South for a series of readings and speaking engagements. Zora offered to give Langston a lift to Tuskegee, and the two set off in Zora’s old Nash coupe, nicknamed “Sassy Susie”.

The writers spent several weeks together on a road trip that sealed their friendship and led to creative collaboration and, years later, a falling out. Between his public appearances, Langston joined Zora on her fieldwork — documenting folk songs, oral tales, proverbs, and ritual practices of African-American communities in the rural South. Langston later wrote of Zora’s ethnographic landscape in his memoirs: “Blind guitar players, conjur men, and former slaves were her quarry, small town jooks and plantation churches, her haunts.”

When one considers that Zora was collecting black folklore in the American South under Jim Crow segregation laws — and in the midst of the ‘second wave’ revival of the Ku Klux Klan that swept through the South in the 1920s — the magnitude of her work becomes even more apparent.

Zora Neale Hurston and Langston Hughes had first met two years earlier in New York at 'Opportunity' magazine’s literary awards ceremony, where Hurston had won second prize for her short story, ‘Spunk’. Hurston was offered a place at Barnard College and went on to study anthropology under the mentorship of Franz Boas, one of the most influential anthropologists of the 20th century. Hurston and Hughes kept writing, and soon became central literary figures of an exhilarating cultural period known as the Harlem Renaissance.

The Harlem Renaissance was a burgeoning of African-American creative energy — a literary, intellectual, and artistic awakening that sought to redefine black identity while overturning black stereotypes and racist notions in cultural creation. The neighbourhood of Harlem in upper Manhattan was the real and symbolic heartbeat of this cultural resurgence, nurturing the genius of such figures as Louis Armstrong, Josephine Baker, Paul Robeson and Billie Holiday. Besides Hurston and Hughes, prominent writers of the Harlem Renaissance included W.E.B. Du Bois, Jean Toomer, Claude McKay, Nella Larsen and Rudolph Fisher.

The black renaissance in the North was spurred by the beginning of the ‘Great Migration’ — the exodus of millions of African Americans from the South to the big cities of the North. This social phenomenon was later portrayed by the painter Jacob Lawrence in his Migration Series. Hurston cast her social-scientist gaze over the Great Migration and captured its implications on Southern communities in her first novel, Jonah’s Gourd Vine:

“The cry of “Goin’ Nawth” hung over the land like the wail over Egypt at the death of the first-born . . . Railroads, hardroads, dirt roads, side roads, roads were in the minds of the black South and all roads led North . . . Whereas in Egypt the coming of the locust made desolation, in the farming South the departure of the Negro laid waste the agricultural industry — crops rotted, houses careened crazily in their utter desertion, and grass grew up in streets.”

Published in 1934, this semi-autobiographical novel traces the migration of a family from Alabama, where Hurston was born, to the all-black town of Eatonville, Florida, where Hurston grew up. In this early work, Hurston’s use of the ‘black vernacular’ that was to become a trademark of her fiction was already discernible. Hurston incorporated the vocabulary of African American colloquial speech in her writing, interweaving polished prose with the rhythms of everyday expression.

Hurston was also taken by the primal energy of new art forms, particularly jazz — the natural element of her friend Langston Hughes. Merging the raw earthiness of her Southern roots with the syncopated ‘narcotic harmonies’ of jazz, Hurston writes:

“This orchestra grows rambunctious, rears on its hind legs and attacks the tonal veil with primitive fury, rending it, clawing it until it breaks through to the jungle beyond. I follow those heathen — follow them exultingly. I dance wildly inside myself; I yell within, I whoop; I shake my assegai above my head, I hurl it true to the mark yeeeeooww! I am in the jungle and living in the jungle way. My face is painted red and yellow and my body is painted blue. My pulse is throbbing like a war drum. I want to slaughter something — give pain, give death to what, I do not know.”

Langston Hughes, considered the ‘father of jazz poetry’, had described jazz as “one of the inherent expressions of Negro life in America”, in his essay, ‘The Negro Artist and the Racial Mountain’: “...the eternal tom-tom beating in the Negro soul—the tom-tom of revolt against weariness in a white world, a world of subway trains, and work, work, work; the tom-tom of joy and laughter, and pain swallowed in a smile.”

The Harlem Renaissance helped lay the foundations of the Civil Rights Movement, and profoundly shaped African American cultural expression in the modern age. As much as Hurston was a child of the Harlem Renaissance, she was also an anomaly in its literary circles. Most Harlem Renaissance writers strove to create works that demonstrated the respectability of black characters, as a way of countering black stereotypes perpetuated by white cultural production. Their works were mostly set in the Northern cities and portrayed the black individual’s struggle against white society. By contrast, Hurston wrote about the rural South, exploring the cultural fecundity of black communities, penetrating the complexity of human relationships among African American individuals — at times intimate and nourishing, at times destructive and dysfunctional.

Integral to Hurston’s life and ouvre is her groundbreaking work as a folklorist and anthropologist, which moulded and informed her literary work. Among Hurston’s non-fiction achievements are her 1934 essay ‘Characteristics of Negro Expression’ and her 1935 collection of Southern black folklore, Mules and Men. In 1936, Hurston was awarded a prestigious Guggenheim Fellowship to conduct fieldwork research in Haiti and Jamaica on the practice of Voodoo and Obeah. Hurston’s time in the Caribbean — during she which participated in Voodoo rituals and had close encounters with Voodoo priests and zombies — resulted in her pioneering book, Tell My Horse: Voodoo and Life in Haiti and Jamaica. Hurston’s anthropological writings are evocative, a rare blend of ethnographic insight and literary instinct. She observes: “Gods always behave like the people who make them . . . Perhaps it is natural for the god of the poor to be akin to the god of the dead, for there is something about poverty that smells of death.”

Literature was never far from Hurston. While she was immersed studying ritual practices in Jamaica and Haiti, Hurston was also busy writing her second novel, the now-classic 'Their Eyes Were Watching God'. Upon its publication in 1937, the novel was met with mixed reception in Harlem Renaissance literary circles. Some considered Hurston’s portrayal of Janie’s sexual awakening and desires as offensive, while others saw her use of black vernacular as a form of minstrelsy. Among those who sharply criticised the work were two rising stars of African American literature. Richard Wright, who achieved wide acclaim for his social protest novel 'Native Son', called Hurston’s prose “cloaked in facile sensuality” and lamented her unwillingness to write “serious fiction”, while Ralph Ellison, who later wrote 'Invisible Man', called Hurston’s novel “a blight of calculated burlesque”.

Yet there is no denying the power and beauty of Hurston’s most beloved novel, which continues to resonate with readers decades later: “They sat in company with the others in other shanties, their eyes straining against cruel walls and their souls asking if He meant to measure their puny might against His. They seemed to be staring at the dark, but their eyes were watching God.” The criticisms of her peers only highlight Hurston’s distinct path and singular genius, and reveal entrenched sexist attitudes in early 20th-century literary circles, including among progressive writers of the Harlem Renaissance.

Ultimately, Hurston did not seek approval to write, nor did she seek to fit into an image of blackness created by others; her entire life was driven by an irrepressible audacity and spunk. In her autobiography, 'Dust Tracks on a Road', Hurston declares: “I am not tragically colored. There is no great sorrow dammed up in my soul, nor lurking behind my eyes. I do not mind at all. I do not belong to the sobbing school of Negrohood who hold that nature somehow has given them a lowdown dirty deal and whose feelings are all hurt about it. Even in the helter-skelter skirmish that is my life, I have seen that the world is to the strong regardless of a little pigmentation more or less. No, I do not weep at the world—I am too busy sharpening my oyster knife.” – The Vibes, January 31, 2021