“Modernity is the transitory, the fugitive, the contingent, half of art, the other half of which is eternal and immutable.”

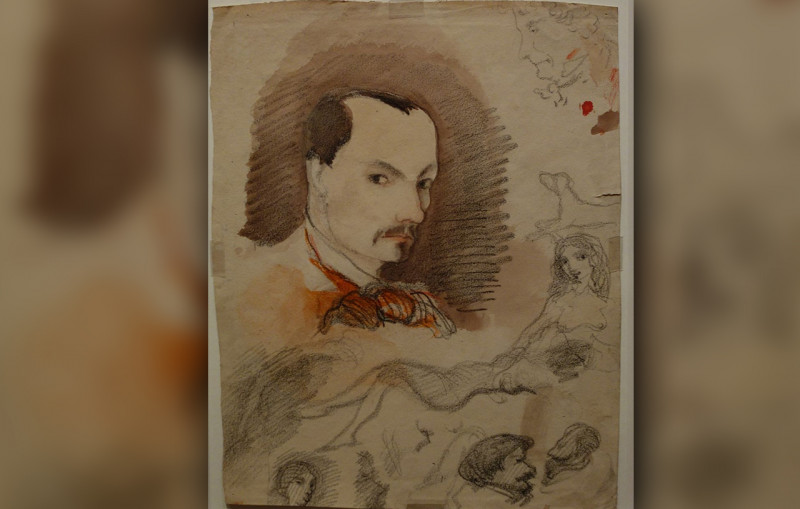

~ Charles Baudelaire

IN July 1858, the French novelist Gustave Flaubert wrote a letter to the poet Charles Baudelaire, with these lines of praise: “You have found a way to inject new life into Romanticism. You are unlike anyone else. You are as resistant as marble and as penetrating as an English fog.”

One year earlier, both writers had been put on trial, respectively, for ‘insulting public decency and religious morality’ – Flaubert for his novel ‘Madame Bovary’, and Baudelaire for his poetry collection, ‘Les Fleurs du mal’ (Flowers of Evil). The court had condemned the ‘overt sexuality’ in Flaubert’s novel and his female protagonist’s rejection of traditional social values. In Baudelaire’s case, it banned six poems that featured elements of lesbianism, vampirism, and dark eroticism – a ban that was only lifted in 1949.

The controversy surrounding the publication of Baudelaire’s ‘Flowers of Evil’ in 1857 contributed to his reputation as a ‘poéte maudit’ (accursed poet): a social outcast, poor and misunderstood, consumed by intoxication and vice. Baudelaire himself helped to mould this image, declaring in the epilogue that “candour and goodness are disgusting”, and depicting his poetry as a “firework of monstrosities”. While this notoriety earned him much attention, it tends to eclipse the profound ways in which Baudelaire revolutionised modern French, and European, poetry.

As Flaubert had perceptively commented, Baudelaire’s poetry revitalised the aesthetic tradition of Romanticism. Baudelaire did not abandon traditional techniques altogether. Rather, he mastered and applied traditional poetic forms such as alexandrines, thoroughly recasting them with startling reconfigurations of ‘beauty’ as he turned his uncompromising gaze on the darkness and filth of modern urban life. 'Flowers of Evil’s' prologue poem, ‘To The Reader’, opens with the lines:

Infatuation, sadism, lust, avarice

possess our souls and drain the body’s force;

we spoonfeed our adorable remorse,

like whores or beggars nourishing their lice.

Baudelaire’s concept of beauty departs radically from the lofty aesthetic ideals of Classicism and the solitary melancholic musings of Romanticism. Baudelaire’s beauty is revealed in darkness and decay, in the sordid heat that pulsates beneath the cold veneer of civilised society. For Baudelaire, beauty must be wrested from the depravity of modern life itself; it is not to be found in an abstraction of divinity but in the incarnate intensity of human flesh and the worn stones of the modern city.

Between the intoxicated dream and the infernal nightmare, beauty is glimpsed, if not born whole. Fleeing existential ennui and the vileness of modern reality, the poet pursues beauty, only to discover her diabolical nature.

For Baudelaire, beauty must be wrested from the depravity of modern life itself; it is not to be found in an abstraction of divinity but in the incarnate intensity of human flesh and the worn stones of the modern city.

A decade before the publication of ‘Flowers of Evil’, Baudelaire was already formulating his concept of beauty in the age of modernism. In his essay ‘Salon de 1846,’ he asserts that beauty is forged in the furnace of the absolute and the particular, the eternal and the transitory.

It is in the interstices of profane, mundane reality that beauty, and heroism, exists: “The spectacle of elegant life and of the thousands of existences which float in the underground of a big city – criminals and kept women – the Gazette des Tribuneaux and the Moniteur prove that we have only to open our eyes in order to recognise our heroism.”

One of the closest readers and most insightful interpreters of Baudelaire’s work was the German literary critic and philosopher, Walter Benjamin. For Benjamin, Baudelaire grasps in his art nothing less than “the continuous catastrophe” of the modern human condition. Baudelaire embodies the archetypal figure of the flâneur, the artist-poet who strolls the modern city as an astute observer and chronicler of modern life.

For Benjamin, modernity is characterised by ‘Chockerlebnis’ (shock experience), the sensory bombardment of modern city life. Only great art that reflects the fragmentary contradictions of modern existence, like Baudelaire’s poetry, can deliver us from an incessant sequence of ‘Erlebnis’ (momentary experience) to a deeper ‘Erfahrung’ (experience that has been lived-through).

...‘Tableaux Parisiens’ is a compelling critique of the renovation of Paris as a playground for bourgeois society and a eulogy to the city’s forgotten people – beggars, orphans, prostitutes, labourers, slaves from France’s African and Indian Ocean colonies.

Benjamin emphasises Baudelaire’s role as a social poet who bears witness, like Benjamin’s ‘angel of history’, to the ruins of Paris left by the storm of progress. For Benjamin, the poet-flaneur hovers at the threshold between past and present, a rag-picker who salvages and invokes meaning from remnants of former life.

Nineteenth-century Paris was being transformed by ‘Haussmannisation’, referring to Baron Georges Haussmann’s extensive redesign and renovation of Paris. While this massive urban renewal saw the construction of wide boulevards and public parks, it also pushed working-class quarters and slums away from the city centre, perpetuating and exacerbating class divides.

Following the trial of ‘Les Fleurs du mal’, and the removal of the six banned poems, Baudelaire added 35 new poems, including a cycle of 18 poems called ‘Tableaux Parisiens’, to the 1861 edition. Charting the alienation of the individual in the modern city, ‘Tableaux Parisiens’ is a compelling critique of the renovation of Paris as a playground for bourgeois society and a eulogy to the city’s forgotten people – beggars, orphans, prostitutes, labourers, slaves from France’s African and Indian Ocean colonies. In his magnificent poem ‘The Swan’ (Le Cygne), Baudelaire walks in the footsteps “of those who lose what cannot ever – ever – be retrieved”:

Paris changes, but my sombre mood

does not. New palaces, old suburbs, blocks

and scaffolding strike me as allegorical,

my memories heavier than rocks.

Haunting the streets and arcades of Paris, Baudelaire, as flâneur moves anonymously among the crowd yet, remains estranged; he keeps a distance and does not completely dissolve into the crowd. In a later essay, ‘Painter of Modern Life’, Baudelaire develops his ideas about ‘la foule’ (the crowd), as the natural habitat for the modernist solitary poet. Baudelaire’s solitude is rooted in, yet breaks, with the tradition of Romanticism.

Baudelaire’s solitude is not that of the lone wanderer, but that of the flâneur-poet submerged in the throng of the city in search of the fleeting face beauty in the cracked mirror of contemporary reality: “The crowd is his element, as the air is that of birds and water of fishes. His passion and his profession are to become one flesh with the crowd. For the perfect flâneur, for the passionate spectator, it is an immense joy to set up house in the heart of the multitude, amid the ebb and flow of movement, in the midst of the fugitive and the infinite.” – The Vibes, April 10, 2021

Notes:

- Excerpt of ‘To The Reader’ by Charles Baudelaire, translated by Robert Lowell

- Excerpt of ‘The Swan’ by Charles Baudelaire, translated by Julia Deakin