THE consensus among poll-watchers is that it will be a close outcome after the ballots are counted and results announced this weekend: a finish too close to call.

But what happens if none of the coalitions crosses the magic line of 112 seats? How would the new prime minister be appointed?

The critical point to keep in mind is that the new prime minister must represent the popular will. He must enjoy the mandate of voters who just expressed their choice in the ballot box.

The legal position is clear.

Article 43(2)(a) of the federal constitution provides that the Yang di-Pertuan Agong shall first appoint a prime minister who is a Dewan Rakyat member, “who in his judgement is likely to command the confidence of the majority of the members of the Dewan”.

This goes to the heart of parliamentary democracy, not just in Malaysia, but across the globe – whether practised in the Westminster tradition or otherwise.

Unlike the presidential system, in Malaysia the government is responsible and accountable to the elected House– the Dewan Rakyat in particular – to get legislation through including the annual budget.

Hence, it is a condition precedent for the person appointed as prime minister that he or she must at all times enjoy the confidence, that is, support of at least 112 members of the 222-strong Dewan Rakyat.

Guidance should be sought from the experience of other Commonwealth countries which share a similar system as ours.

Perhaps the closest example would be the position in February 1974 when then prime minister Ted Heath lost his majority in the United Kingdom’s general election.

The results were as follows :

Labour - 301

Conservative - 297

Liberal - 14

Others - 23

The former Conservative prime minister, Ted Heath resigned although there were talks with the Liberal party to form a coalition.

Instead, Harold Wilson, the leader of the largest party, was invited to form the government. Labour was short of the majority of 318 seats, but because it was the party with the largest number of seats, it was asked by Queen Elizabeth II to form a government.

Its margin over the Conservatives was just 4 seats; but a coalition between the second and third largest parties would have resulted in 311 seats, 10 more than Labour.

Yet Labour was tasked to form the administration.

A strong convention has developed in many parliamentary democracies: when no party or coalition is able to reach the magic 50% plus one seat to form the majority in the elected House, the constitutional monarch (like the UK) or head of state (like the president in India) will appoint the leader of the party or coalition that has the highest seats. Simply because that person enjoys the mandate from the voters in the just concluded general elections to be given the first opportunity to form a cabinet, and then when Parliament is in session (typically a month or two after general elections) to secure a motion of confidence in the elected House.

Relevant passages from leading constitutional works in the UK, Canada and India are reproduced in the appendix hereto.

It is merely another application of the “first past the post” principle which underpins our electoral system.

Applying that convention here would mean that among the three realistic candidates for the office of prime minister are the presidents of the respective coalitions – namely Datuk Seri Ahmad Zahid Hamidi, Datuk Seri Anwar Ibrahim, and Tan Sri Muhyiddin Yassin.

The person whose coalition wins the highest number of seats must be appointed prime minister even if their coalition does not secure 112 seats as soon as it is convenient (typically in Malaysia, the following day – Sunday, November 20).

He can then form a cabinet and build up numbers to secure a motion of confidence by the time Parliament meets.

Appointing any other candidate would be anti-democratic, and would be repugnant to the wishes of millions of voters who had just cast their ballots.

There is no legal or political reason why this long-standing convention cannot be applied to Malaysia on the evening of the 19th and the following day.

In order to depersonalise the discussion, let us call the three candidates Mr X, Mr Y and Mr Z.

It would be unconstitutional if Mr X’s coalition were to secure 80 seats, Mr Y’s coalition 45 seats, and Mr Z’s coalition the balancing 40 seats, out of the 165 seats in the peninsula (there are 31 in Sarawak, 25 in Sabah and 1 in Labuan) – and Mr Y is made the prime minister simply because he claims Mr Z also supports him, giving him a total of 85 seats.

Instead, the only constitutional option in this rhetorical example would be for Mr X to be appointed prime minister because his coalition was the most popular – thereby earning him the first right to form a government, and secure support from another 32 seats by the time Parliament is convened.

Mr X is entitled to a fair trial in government, at least until it is clear by a confidence defeat that he does not enjoy support in the Dewan Rakyat.

Furthermore, two or three parties in Sabah and Sarawak may join Mr X’s coalition, or at least not vote against him in a confidence motion, thereby ensuring Mr X’s government comfortably remains in power for some time.

Needless to say, if Mr Z’s coalition secures 112 seats, the palace must call him. In that scenario, there is no other option – Mr Z must become Prime Minister.

It must always be kept in mind that the Yang di-Pertuan Agong, like other constitutional monarchs, cannot bring his personal preference into the decision-making. Agong must be above party politics and represent national interest.

Further, the palace must not be involved – directly or indirectly – in bargaining and negotiations that may take place after the results are known. That is solely for the politicians to sort out.

Finally, because millions of Malaysians would have just voted, the wishes of the majority must be respected by the palace. After all, that is why we have a system of government by parliamentary democracy in the first place. – The Vibes, November 15, 2022

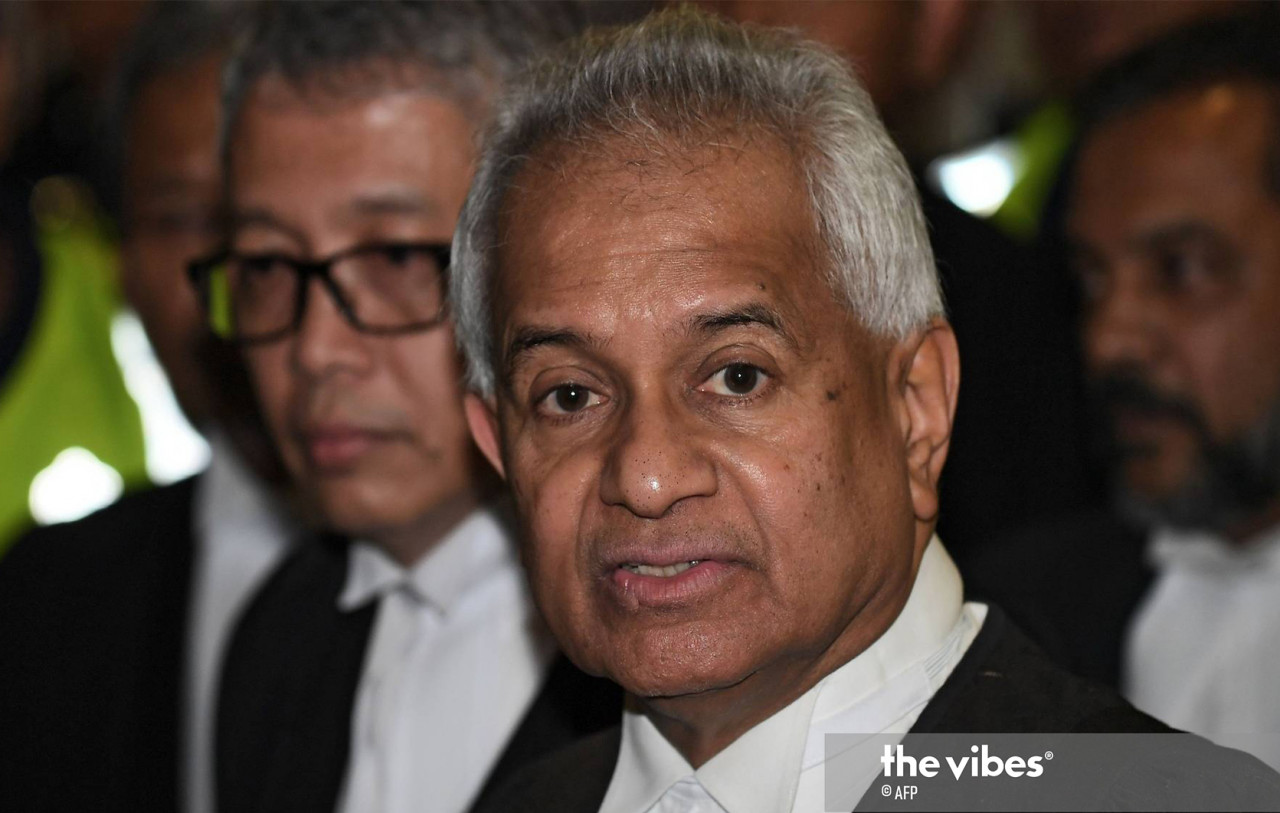

Tan Sri Tommy Thomas is a former attorney-general. He has included references below to support this article

Appendix

UNITED KINGDOM

CONSTITUTIONAL AND ADMINISTRATIVE LAW

Stanley de Smith and Rodney Brazier

8th Edition, 1998

Pages 168 and 171

“The general rule is that in appointing a Prime Minister, the Queen should commission that person who appears best able to command the support of a stable majority in the House of Commons.”

“Hence the Queen is unlikely to have to exercise a personal discretion again unless no party has an overall majority in the House... in such a situation her duty will be to take such counsel as is proper and expedient to assist her in deciding who is the most appropriate person to invite to form a Government with a reasonable prospect of maintaining itself in office. That person will normally, but not invariably, be the leader of the largest party in the House of Commons.”

(my emphasis)

CANADA

CONSTITUTIONAL LAW OF CANADA

Peter Hogg

(5th Ed, 2008)

Ch. 9.7(b)

“… the appointment of a new Prime Minister has to be made by the Governor General. This decision is always a personal one in the sense that the Governor General does not act upon ministerial advice. But other conventions of responsible government have now severely limited the discretion that the Governor General really possesses. The Governor General must find the person who has the ability to form a government which will enjoy the support of the House of Commons. The only person with this qualification is the leader of the party which has a majority of seats in the House of Commons. Moreover, each Canadian party has procedures for selecting its own parliamentary leader. This means that in most cases the Governor General’s ‘choice’ is inevitable.”

(my emphasis)