FOR as long as I could remember, I’ve always felt different.

It won’t be too far of a stretch to say that I live a lot in my head. Existing between my thoughts and reality. In my head, I’ve almost always raced through everything that I need to achieve – no matter the degree of complexity. Though, in reality I’m constantly waiting for my body and actions to catch up with my thoughts – it could take years, so don’t count on me to think quickly.

I don’t always understand intuitively what is easily understood by most. I always had to pretend that I do, to appear well put together. This is a concept known as masking, which makes autism in females harder to be diagnosed. I don’t always get the punch line (what was life before Google and a smartphone?) and sarcasm flies over my head.

For a strangely smart person, I’ve never quite shrugged off my naïveté; I often take what anyone tells me at face value. I am constantly guessing what the right answer is to every interaction and the debilitating anxiety to ‘arrange’ my face to match my responses. This means I often can’t match what I feel to what I say, so I can come across as being awfully mean when I laugh at your misfortune.

All these make navigating life extremely stressful. I feel like I’m constantly asked to make a U-turn and in a permanent loop to please try again. When I received my diagnosis of being autistic at 36, it was as if someone had finally whispered in my ear that I may now pass Go and collect my two hundred dollars. I could proceed with life now.

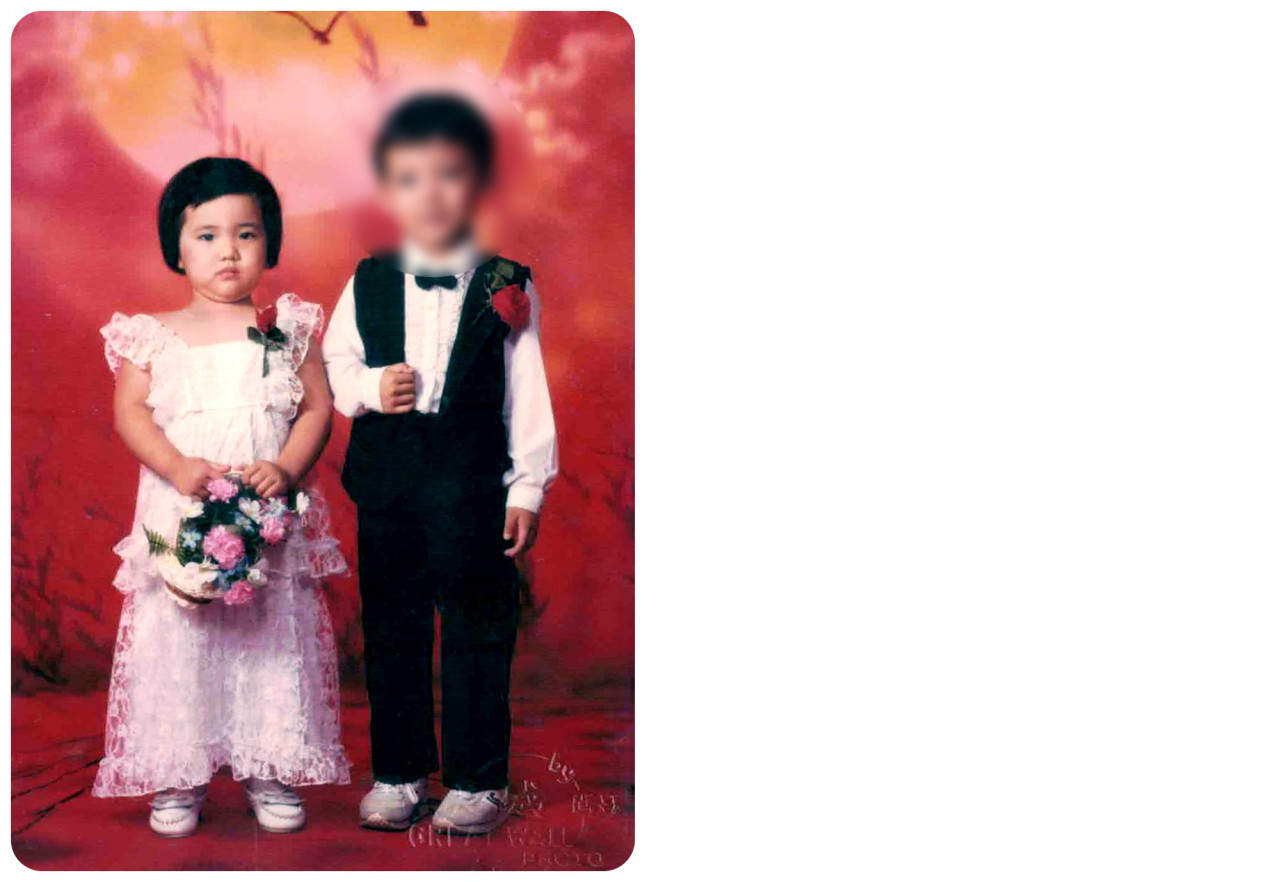

Looking back at my childhood photos now, I see with new eyes that I’ve always looked distracted and aloof. There’s this specific photo taken of me dressed up as the flower girl at an aunt’s wedding.

I was in a white lace dress, most certainly polyester, and I had the widest scowl on my carefully made-up face. I distinctly remember the excruciating itch and how uncomfortable I felt. It was a painfully long negotiation with my mother to get out of what I now know as a sensory hell of a dress. These days, I only wear the same few t-shirts and my denim. It feels the same, it looks the same, and it's safe.

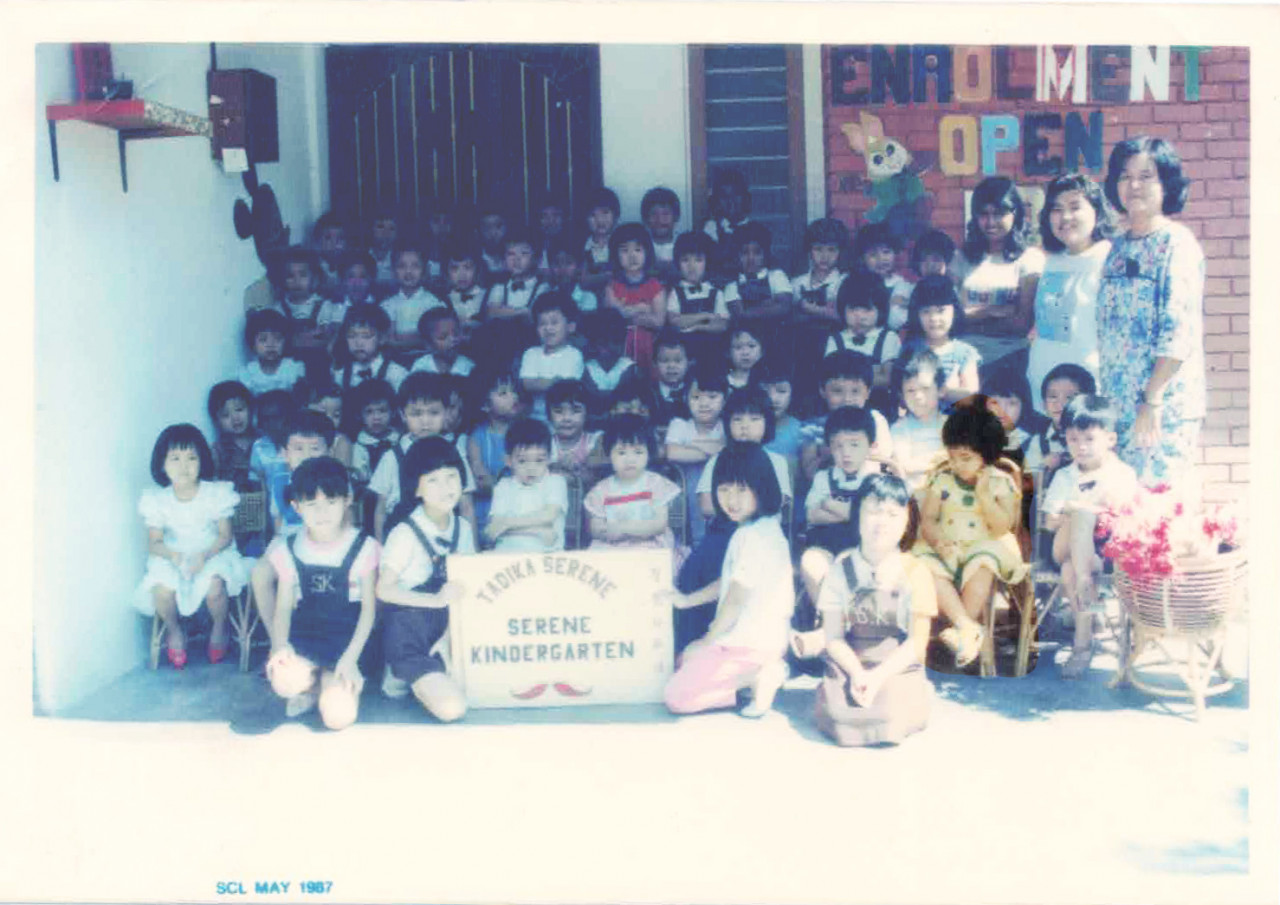

I was inattentive, disruptive, fussy, and deeply troubled in my schooling years. I terrorised my teachers and challenged the school’s rules at every turn I could. How would it matter if I wore a silver hair clip on my own head or if I did not want to wear my shoes today? I often got so bored and tired of school; I learned to simply walk out of the front gate to hide in a cement tunnel at the playground across the street.

I also spent a lot of time hiding out in toilets – a habit I carry through till today. None of these behaviours were alarming then because I did extremely well in school. I was excused and tolerated for it, as long as I was getting A’s, then I must be okay.

My ability to hyperfocus and my obsessiveness got me through school, university and to some degree, my earlier career path. Though it wasn’t without a huge toll on my mental health as every milestone I pushed myself through, is often followed by a shutdown that could last months or even years.

A psychiatrist that saw me while I was in university assured me that I would grow out of it. I’m 38 today and I am still waiting for that moment.

The next time I would see a psychiatrist, I was in an emergency ward after a series of meltdowns and the breakdown of my mental state. I was going through a particular difficult period of adjustment in my life then. If you’ve never been to a hospital’s emergency care, it’s a sensory nightmare. The bright fluorescent lights, loud nurses, and arctic-like temperature. It would drive any sane person catatonic. I was diagnosed with schizophrenia in a mere 15-minute consultation. It was a conversation that I would remember for a long time.

“Do you hear sounds?”

“Yes, I do”

(Don’t we all, but I never thought to ask her to clarify what kind of sound she meant because she looked like she was in a hurry).

“Do you think you’re safe?”

“No, I’m scared”

(Because I was there with a man that I was in a confusing relationship with, and he was in the consultation room with me. I believe she mistook this as the sounds I hear are harming me.)

Had I understood what was implied then, perhaps my life’s trajectory would’ve been different. This is a common barrier with autistics and communications. In being literal and not understanding the subtext of what’s being asked of us, our responses are often misunderstood. The inability to sometimes discern what information to disclose becomes detrimental to how we are being perceived by others.

Shortly after that diagnosis, I was admitted into the psychiatric ward as I showed no improvement under medication. I was put through multiple sessions of controversial electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) treatments – of which was consented to by my next of kin without so much as an understanding of what it is other than “She needed it as what she has is very strong in her head”.

What would someone in that position make of that statement other than to say, “Please do what you feel is right for her”.

Throughout this admission, I learned very quickly how little autonomy you have in your treatment plan and how very little dignity you will be left with in the way you are restrained to your bed should you resist instructions. You do learn very quickly to feign compliance and stop communicating so you could be discharged quickly and be on your way out.

This is what they would then term as 'recovery'. From thereon, I had a string of other diagnoses with many different professionals. I often joke that my diagnosis of ASD that came 11 years after that admission, is the bonus one for having my card stamped in full.

I never had or found much social support. In college, when a group of girls I used to believe were my friends unceremoniously ousted me from their group through an ex-boyfriend who also broke up with me via a telephone call while having tea with the lot – it took a long while to register that I was no longer part of that group.

This cycle of not being able to hold on to any form of friendships is deeply marred by my inability to navigate these invisible social rules that drive these relationships. While I often feel left out and isolated, it’s always a precarious balance of being relieved of the obligations to maintain these relationships, while also finding space for my solitude.

As a modern Asian female, we are ridden with multiple layers of social expectation. What more the added nuance of experiencing life as an autistic person. I pile on unreasonable demands on myself to try harder to fit into this society. An innate need to catch up with life in attempts to put behind the schizophrenia diagnosis and psychiatric ward admission. Traumatised by that experience, I found myself hiding parts of myself that were deemed troubled and unacceptable. I have come to believe the worst things that have been said about me.

With these prolonged masking and troubling maladaptive behaviours that I’ve picked up along the way to cope, my world began to fall apart slowly. The breaking point was cemented by a deeply troubling and abusive relationship with a man who struggles with an addiction. You will find that many autistic women often find themselves in positions of vulnerability with abusive or toxic partners. Domestic violence involving autistic women is also a common narrative.

Any decent therapist will tell you that years of masking and trying to conceal who you are to be accepted is often a recipe for disaster. In being so profoundly isolated and fighting loneliness with no way of verbalising your innermost thoughts nor an understanding of why you feel the way that you do; you lose sight of the person you are. When you’ve lived so long being told that the person you are is not welcomed in this world, you will try to adapt and find ways to belong. As humans, it is an innate sense in all of us to search for a sense of belonging. It is what drives our purpose here on earth as humans.

When I first sought my autism diagnosis, I had thought it was a way for me to stop being so misunderstood and to find ways for me to belong in this. As it turns out, it had been a path to finally be my own person and re-learning a way to lead my life kinder and gentler.

The diagnosis also gave me a path to re-evaluate my past relationships, friendships and all the broken connections. Instead of living with shame, I can now see where my social naivete was and to forgive myself for what I could not have possibly understood, as well as feeling vindicated for where I now see I was being bullied. It is empowering when you understand why you made the decisions that you did.

In accepting and knowing that I was autistic all along, I now see why my life is always a string of crises. Experiences that most people take for granted will often be magnified for me. The first concern I’ve raised to the neuropsychologist was if she knew that autistic women are 4 times more likely to die by suicide. It scares me till today to learn that crisis support for people like me do not exist.

In my attempts to seek help, I had been turned away multiple times by general practitioners, therapists, and emergency wards as so little was being understood about presentations of autism in women like me. An MO from the emergency ward at a private hospital chided me in a public waiting room and told me it was not possible for me to be autistic because I am educated, and I could get to the hospital on my own. I meet psychiatrists, psychologists who would insist on a ‘personality disorder’ as the right answer before autism is considered. I am too well spoken to be autistic.

On the flipside, I look back at all the time when my words fail me. I was mute when I sat by my grandfather who died from a heart attack, I was mute when I was sexually abused as a child, I was mute when I was hit by partners, I was mute when I am often wronged and misunderstood in the eyes of the public. Most autistic women would come to live a life between the intersection of autism and trauma.

This diagnosis is not a magic wand that makes everything better but women like me should also not need to continue with our battle cry for us to be taken seriously and be understood better. We must begin to question our gender bias in diagnosing females. We must learn and begin to see beyond what’s unsaid and to rethink the diagnostic tools available and the acknowledgement that the current diagnostic criteria is in favour of the stereotypical white-Caucasian male stereotype.

Today, on this one day where the world dedicates its attention to autism, I implore that we look around us and reconsider the space that we give to the stories and narratives of autism.

The conversation on autism in Malaysia is also often drowned by a dominant focus on children and early intervention. I was perplexed when the neuropsychologist that diagnosed me could not point me to where I could go for help aside from 'perhaps just therapy' and a few suggestions to centres that caters towards children. Do children not grow up to be adults?

My story is unique but it’s not uncommon. In the past year, being equipped now with the vocabulary and language to describe myself, I had the opportunity to look for and connect with other women like me. In learning now that I do belong and there is a tribe of us, it gives me back a voice to advocate for myself and for me to be my own person living my truth.

The term 'lost girls' is often used to describe women like me who found their diagnosis later in life. I don’t want to paint a picture of triumph or that autism is my superpower but neither do I want to paint it as a tragedy. Autism is complex and we must start acknowledging that the narrative on autism is largely spoken of by how society experiences their interactions with us, not how we truly feel or see ourselves.

In advocating for Autism Awareness, we must also remember that acceptance is key to those who are unlike us and that there is no one way to be a person. The world has enough space for all of us to co-exist and live the life that we each deserve, and if it doesn’t, then it is on us to make space. – The Vibes, April 2, 2022

Beatrice Leong is a documentary filmmaker and entrepreneur attached to a health tech startup initiative

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) is a complex developmental condition which involves persistent challenges with social communication, restrictive interest and repetitive behaviours.

There is a persistent misunderstanding that autism is rare in women as female presentations are often much more nuanced and their ability to 'mask' to fit in with their peers, often only manifest in mental health challenges and crises later in their lives.

This month’s series on women with ASD, often known as 'The Lost Girls' by Beatrice, highlights new narratives and perspectives of autism from the inside.

_-_SYEDA_IMRAN_-_26.jpg)